Table of Contents

Displaying Reputation

Three Questions

Okay, so you've designed a reputation model and decided how to collect your inputs. But your work doesn't end there. Far from it. No, now you're faced with a number of decisions about how best to use the reputations that your system is tabulating. Specifically, this chapter and the next will discuss your many options for using reputation to improve the user experience of your site, enrich content quality, and help educate and provide incentive for your users to become better, and more active, participants.

We'll walk you through a simple process for deciding how best to use reputations. We'll start with three simple questions:

- Who will be able to see the reputation?

- Is it personal-hidden from other users, but visible to the reputation holder?

- Is it public-displayed to friends or strangers, or visible to search engines?

- Or is it limited to corporate use-for improving the site or recognising outliers in discrete ways that may not be visible to the community?

- How will the reputation be used to modify your site's output?

- Will the reputation be used to filter the lowest- or highest- quality items in a set?

- Will items be sorted or ranked using it?

- And/or will this score be used to make other decisions about how the site flows or your business operates?

- Is this reputation for a content item or a person? There are some fundamental differences in approaches for each.

Though you may chose multiple answers from the list above for each of your reputations, try to keep it simple at first-don't try to do too many things with a single reputation. Confounding purposes within a reputation-such as surfacing participation points as a public karma score can encourage undesirable behaviour from your users and may even backfire-discouraging them. Read these two chapters completely to get a better understanding of this and other issues with overloading single reputations with too many jobs.

Resist the temptation to treat a single reputation score as the cure-all for your user generated content incentive ills. Remember the lesson of Chap_1-FICO .

Who will be able to see the reputation?

At this point, the reputations you're calculating are little more than cold numerical scores, rolled up from the aggregate actions of those interacting with your site. You've carefully determined the scope of the reputation, chosen the inputs that contribute to it, and thought at length about the type of community effect that you want the reputation to affect. Now you must decide not only how to display the reputation, but whether it makes sense to do so.

So plan accordingly! The degree to which you display reputation information on your site (and the prominence of said displays) will influence: the actions that people tend to take on your site; their trust in interactions with you, your objects, each other, and their long-term satisfaction with your community.

To Show, or Not to Show?

Before we get into who should see the reputation, let's consider first whether to show it at all. There are some compelling reasons to keep reputations hidden. In fact, there are some circumstances where you may want to obscure the fact that you're keeping them at all! It may sound rather Machiavellian, but the truth of the matter is this: a community under public scrutiny behaves differently (and, in many ways, less honestly) than one in blissful ignorance.

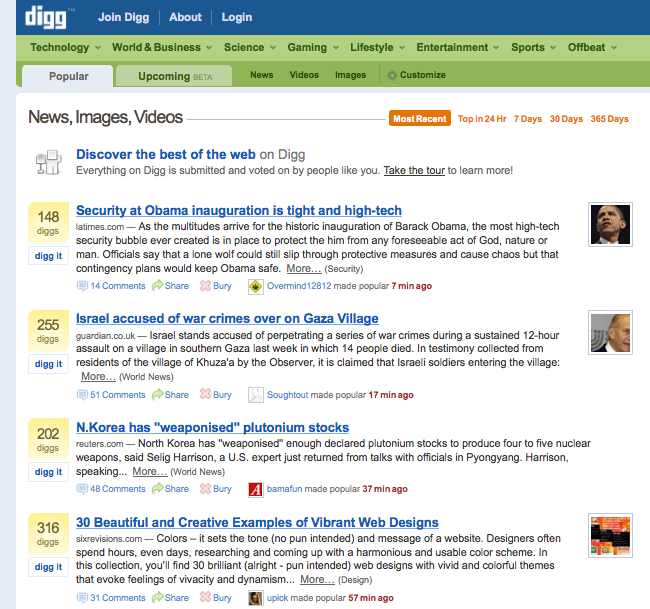

There several trade offs involved. Displaying reputations takes up significant page real estate, user interface design and testing, and can compete with your content for the user's attention and understanding. Real quick: show 10 of your friends Digg.com (Figure_8-1 ) and ask them-what kind of site is this? News? Entertainment? Community? Odds are good that at least a few of them will answer: “This appears to be a contest of some sort.”

This is not a bad thing! But it points out that Digg has made a conscious design decision to prominently display content reputation. In fact, they've made it the central interaction mechanism that orders the site. It's practically impossible to interact with Digg, or get any use out of it, without understanding-to some degree-how community voting affects the selection and display of popular items on the site. (Digg is perhaps the most well-known example of a site that employs the 'Vote to Promote' pattern. See Chapter_7 .)

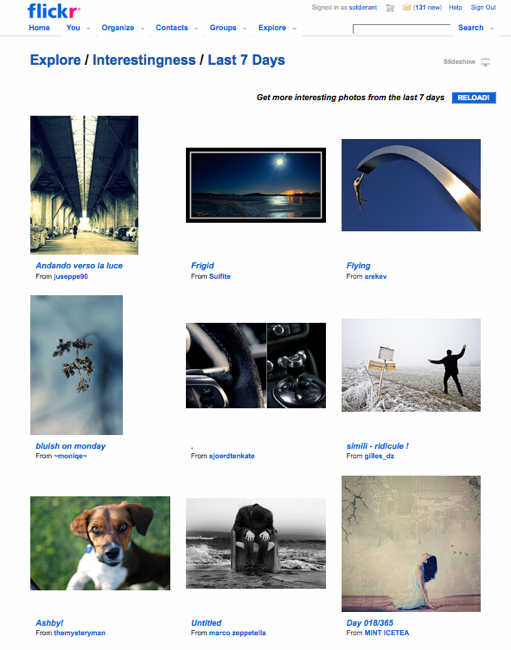

Juxtapose Digg's approach with that of Flickr. The popular photo-sharing and discovery service also makes use of reputation to surface quality content but explicit reputations are not displayed: rather, items that achieve a certain reputation are displayed prominently on the site and can be browsed (on a daily, weekly or monthly basis) in the 'Explore' gallery: http://www.flickr.com/exploreFigure_8-2 . The end result is a very consistent and impressive display of high-quality photos with very little indication about the criteria for those photos' selection.

Flickr's “Interestingness” algorithm determines which photos make it into Explore and which don't. The same algorithm lets users sort their own photos by their Interestingness.

Digg and Flickr represent two very different approaches to reputation display, but its interesting that the results are very much the same: theoretically, you can always glance at the front page of Digg, or Flickr's Explore gallery, to understand 'where the good stuff is' on the site: what are people watching, commenting on, or interacting with the most.

So how do you decide whether or not to display reputations on your site? And with what prominence? Generally, you should follow the rule of least disclosure: do not display a reputation that doesn't add specific value to the objects being evaluated.

Likewise, don't bother asking users for reputation input (Remember inputs? Revisit Chapter_7 for a refresher) that you are never going to use: you'll confuse your users and this will lead to the emergence of undesired patterns of “invented significance”, including abuse.

Avoid collecting reputation that is only for display: Orkut allowed people to explicitly rate other users on iconic dimensions like trusty, cool, and sexy for no utility other than display. This caused all kinds of social backlash as people were either disappointed that they weren't rated cool by more people, or were creeped out by people of the same gender calling them sexy. Eventually, Orkut removed the means for users to determine exactly what their friends rated them.

So, in the end these types of reputations don't mean anything and consume valuable resources. If you don't have a relevance use for your reputation, you'll probably be sticking yourself with a future tough choice of either awkwardly removing a failed feature or having to support it as a costly legacy element.

Personal Reputations: Eyes-only

Are you keeping reputation primarily to educate your users and keep them informed about how well they-or their creations-are performing in the community? Then consider displaying that reputation only to them-keep it as a personal communication between site and user.

Personal Reputation is Not Private

We use personal in a very deliberate sense here, to not conflict with the notion of private. No reputation system is truly private: at least one other party (typically you, the corporation) will almost always have access to the actions, inputs and roll-ups that formulate a user's score. In fact, you may keep corporate reputations (see Chap_8-Corporate_Reputations ) that are largely based off of the exact same data.

So remember, reputations may be for personal display, but that's no absolute guarantee that they're private. As a service provider, you should acknowledge this and account for it in your Terms of Service (TOS)

Personal reputations are used extensively for applications like social bookmarking, lists of favorites, training recommendation systems, sorting and filtering news feeds, providing content quality and feedback, fine-grained experience point tracking, and other performance metrics. Most of the same user interface patterns used for displaying public reputation apply to personal ones as well, but care must be taken to ensure that the user knows when his reputations will and will not be displayed to others.

A reputation should be kept personal when its owner gains some significant benefit from the reputation-it either improves her experience of the site (i.e. personalization) or provides a tool for increased self-satisfaction. For example, selecting news stories about various sports teams over time might generate a geographic region reputation allowing for improved advertising behavioral targeting - clearly this should not be public information, but might be surfaced privately so the user can correct it; “I'm a fan of Northern California sports teams, but I'm going to Harvard and really want ads for electronic stores in the Boston Area.”

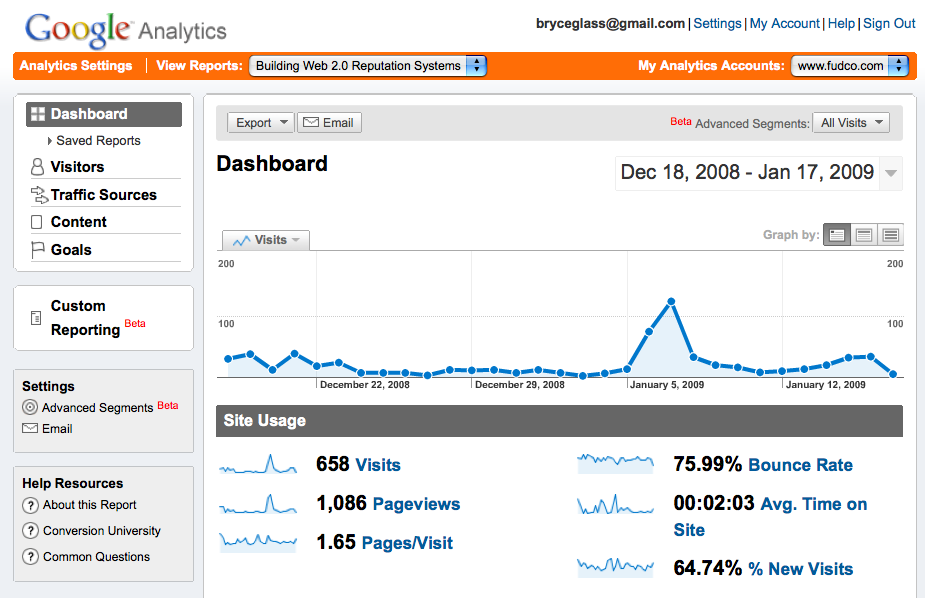

Google Analytics (Figure_8-3 ) is an example of rich personal reputation information. It provides detailed information about the performance of your website, across a known range of score-types, and is only available to you, the site owner (or those you grant access to.) While this information is invaluable to you in order to gauge the community's (in this case, the Web's) response to your content, there's very little practical benefit to exposing it to everyone! In fact, this would be a horrible idea.

Personal and Public

With some reputation display patterns, there is both a personal and a public representation of a reputation. In the case of Named Levels display pattern (detailed below), the personal representation of the reputation score is often numeric, representing the exact score in high precision. The public display obscures exactly where in the level this target's score actually is. Online games usually report only the Level to other users and the exact Experience Points to the player.

Public Reputations: Widely Visible

When the whole community would benefit from knowing the reputations of either people or content, then consider displaying public reputations. Public reputations may be shown to everyone in the community, or perhaps only those that meet a certain criterion: they are in a group or are social-network friends or they themselves have surpassed some reputation-threshold and are senior, trusted members of the community.

When is it a good idea to display public reputations? Remember our original definition: reputation is information used to make a value judgment about a person or an object in a given context for a specific time. So, consider the following set of questions:

- What decisions am I asking users to make on my site?

- Compare items' quality against each other?

- Determine someone's credibility or trustworthiness?

- Decide whether something's worth reading or not?

- Am I asking users to make time-sensitive decisions, or decisions where additional information, well-placed would save them a lot of heartache?

- Can I present the reputation in a way that is fair, comprehensible, and doesn't overwhelm the simple presentation of the content?

Depending on your answers to the above questions, you may want to display reputations publicly on your site. We'll discuss some options for how to display reputation below.

Public reputations are used for hundreds of purposes on web to compare items in a list based on community member feedback, evaluate particular targets for online transaction trustworthiness, filter and display only top rated message board posts, rank the best local Indonesian restaurants, show today's gallery of the most interesting photos, leader boards of the top reputation scoring targets, and so many more.

Over time, public reputations can evolve to represent your communities' understanding of it's own zeitgeist. And there's the rub-depending on how you use public reputation, you can alienate those who aren't a part of the crowd. Yelp is all about public ratings and reviews of local restaurants, but it isn't used extensively by users over 50 as the bulk of the reviews are written by 20-somethings who are perceived as being more interested in the restaurants potential as a dating hangout.

Public reputations are useful for allowing your community members to make comparisons between like items. Public karma reputations also serve as an effective extension of a person's identity.

Corporate Reputations: Keep it on the Down-Low

Almost every website with a large volume of user generated content is using hidden, corporate reputation-a means of tracking exactly who is saying what about a piece of content or another user.

- When a user presses the “Spam” button in web mail, they are helping to create an IP address database of abusive mail servers.

- Web crawlers constantly scan the web to examine what sites link to what other sites and calculate a hidden score like Google's Page Rank to be used to rank search results.

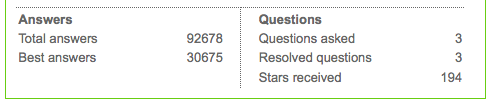

- Yahoo! Answers keeps corporate reputation about users who are particularly good at identifying bad content submitted to their site and gives those users more power to hide it quickly.

And these corporate reputations need not always be ones that scripts or bots act on immediately-they can also be a very a helpful tool for human decision making: community managers often get secret reputation reports of the most active, connected, and highest quality user contributions and creators for their site.

They might use this information to generate high-quality 'best of' galleries to promote the site, or perhaps invite top contributors to participate in early testing of new designs, products, or features. Finally, user actions are often aggregated into reputations for advertising behavioural targeting, customer care planning and budgeting, product feature needs assessment, and even legal compliance.

Even if your site wouldn't benefit from any public or personal form of reputation display, you probably need corporate reputations to understand what your users are doing and to tune your site development and optimise support costs appropriately.

How will the reputation be used to modify your site's output?

After deciding who will see which reputation scores, you'll need to decide how they will be used to change the way your application works. It's easy to think that all you need to do is display a few stars here or a few points there and assume you're done-but you'd be missing out on capturing the most value possible out of your reputation.

When utilizing reputation in this way, it is important to remember that we're talking about how to identify the outlying reputable entities (users and content) in order to improve the quantity and quality of interaction at your site. As such, it is critical to review the goals you set for your system back in Chapter_6 when selecting the patterns. If you're primarily concerned about identifying abusive behavior, you'll want to focus on Filtering and Decisions. If you're going to be displaying a lot of public reputation over a large set of entities, you'll probably want to focus on Ranking and Sorting to help users explore your content.

The patterns for leveraging the reputation on your entities are explained in detail in Chapter_9 .

Reputation Filtering

At it's simplest, filtering is simply sorting on one or more reputation dimensions and looking only at the top, or bottom, entries of the list to identify the highest and lowest scoring entities for potential further, even automatic, action. In reality, many reputations used for filtering are often made of more numerous and complex inputs than those reputations that are built for public display in ranks or sorts.

Consider Flickr's Interestingness filter reputation: it is corporate (not displayed to any user); it is complex (made up of many inputs: views, favorites, comments, and more); and it is used to automatically and continuously generate a public gallery. But the score is not used for any other user-facing purpose. You cannot 'query' a photo to get its interestingness score. Perhaps the easiest way to think about a filter reputation is that, if it is not ever displayed to users, it's composition does not have to be understood by them. If users can see a reputation they'll want to know what it means - and part of that understanding will be a strong desire to understand how it is calculated.

In fact, algorithm-speculation has almost become a form of community sport on the Web. Name any popular reputation-heavy site out there (Digg, Amazon, YouTube and on and on): odds are good that you'll find any number of threads or forums dedicated to figuring out exactly how its algorithm works.

The specific reputation usage patterns related to filtering are: User Threshold, Public Gallery, Guided Learning, Recommendations, Bookmarks/Favorites, Similar Items, Experts: Content by Author Karma, Friends Filtering

Reputation Ranking and Sorting

By far the most common displays of reputation are in the form of explicit lists of reputable entities, such as the restaurants in the local neighborhood with the highest average overall rating, or the list of players with the highest Elo ranks for Chess, or even which keyword search marketing terms are generating the most clicks per dollar spent.

Typically, the reputation score is used alone or in conjunction with other meta-data filters, such as geographic location, to make it easy for users to sort between multiply entities at a single glance. The primary purpose of these sorts is to provide information for the user to select an item to examine at in more detail. Note that the reputation score need not be displayed in order to accomplish a sort or rank entities. For example, public search engine ranking scores are typically not displayed in order to discourage search engine abuse.

Any time you sort or rank reputable entities, you're helping users sort data into the good and the bad. This is creating value-and wherever there is value created there will be people interested capturing as much of it as possible using whatever means available. The more successful your reputation ranking is, the more value it creates, and the more some people will want to twist your design to their own benefit.

The lesson: Reputation based displays that may work for small communities may not socially scale well with success and will need to be modified over time. Keep an eye out for use patterns that don't contribute to your business and community goals.

Recommender systems use reputation to make suggestions about similarities between user tastes: “People who likethe same things as you do you also like…” and discovered taste similarities between items: “People who liked this item, also like…”. They use reputation in the form of confidence scores and typically display multiple entities in rank order when making recommendations. When the user selects a suggested item, that selection itself is also input into the reputation system to further improve the quality of future results.

The specific reputation usage patterns related to ranking and sorting are: Quality-Sort SRP, leaderboards, Related Items, Recommendations, Search Relevance (i.e. Google's Page Rank), Corporate Community Health Metrics, Advertising Performance Metrics.

Reputation Decisions

This entire class of use patterns is often overlooked because it typically happens behind-the-scenes, out of the direct site of users. Though you may not see it, more hidden decisions are made based on reputation than are actually reflected directly to users either with filtering or ranking.

Billions of email messages are processed daily and the IP addresses of the senders have secret reputation, used to decide if the item should be dropped, put in a bulk folder, or sent on to another content-based reputation check before being delivered to your email box. This is only one example of many patterns used by web 2.0 companies around the world to manage user generated content without exposing the scores or the methods for their calculations. When used for abuse mitigation, the value of the reputation score can be directly correlated with cost savings due to improved efficiencies in Customer Care and Community Management as well as in hardware and other operational costs. Each year, the IP reputation system for Yahoo! Mail saves over a million dollars in real costs for servers, storage, and overhead.

When a reputation score is complex, such as karma (see next section), it may be suitable for public display as a stand-alone score so that other's can make specific, context sensitive decisions. A good example of a publicly shared karma that is used for user decisions is eBay's Feedback and other reputation scores. Since the transactions for items are often one-of-a-kind, content filtering and ranking doesn't provide enough information for anyone to make a decision about whether to trust the seller or buyer.

Of course, some reputation is non-numeric and can not be ranked at all such as comments, reviews, video responses, and meta data associated with the user that generated the reputation. These forms must be displayed in order to be interpreted by the user directly. For instance, a 20-year old single woman in Los Angeles who is looking for a new sweater might want to discount the ratings given by a 50-year old married man that is living in Alaska. Non-numeric reputation often provides just enough additional context for people to make smarter judgements about your entities.

The specific reputation usage patterns related to decisions are: Critical Threshold, Automatic Rejection, Flag for Moderation, Flag for Promotion, Reviews and Comments

Content Reputation is Very Different from Karma

We use the term reputable entities to describe everything that has a reference in your database that has one or more reputations attached. This generalization includes users and content items. As such, you might think that all kinds of reputation score types and all kinds of display and use patterns are equally as valid for content reputation and karma-in practice, however, this is usually not the case. In order to highlight the differences between content reputation and karma, we need to categorize the ways they are calculated to include the ideas of simple and complex reputation.

- Simple Reputation

- Any reputation score that is generated by direct user evaluation of a reputable entity and subject to an elementary aggregation calculation, such as simple average. For example, this is what most ratings and reviews sites use. Simple reputation is a direct evaluation that is aggregated in a simple-to-understand manner.

- Complex Reputation

- An aggregation of multiple evaluations, including evaluations on different, but related, targets that may have an opaque aggregation calculation method. Email IP Spammer, Google Page Rank, and eBay Feedback reputations are examples of complex reputation. It is an indirect evaluation, and how it was calculated may not be understood by its users, even if displayed.

Content Reputation

Content reputation scores may be simple or complex. The more simple the score is-that is the more that it directly and understandably reflects the opinions or values of your users-the more ways you can consider using and presenting them. You can use them for filters, sorts, ranks, and in many kinds of internal and personalization decisions. For most sites, content reputation does the heavy-lifting of helping you to find the best and worst items for appropriate attention.

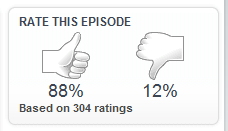

When displaying content reputation, avoid putting too many different scores of different types on a page. People easily get confused. For example, on the Yahoo! TV Episode Page the user can give a TV program an overall star rating and individual episodes of the program a Thumbs-Up or Down rating. When examining the data, it became obvious that many visitors to this page are clicking on the thumbs believing they are rating the entire show, and not just a specific episode.

Karma

Content reputation is typically about things, typically inanimate and often emotionally distant. But karma is user reputation and users are people-they are alive, have feelings and provide the very activity that powers your site. Karma is significantly more personal and therefore sensitive and meaningful. If a manufacturer gets a single bad product review on a remote web site, they probably won't even notice. If a user gets a bad rating from a friend-or feels slighted or alienated by the way your karma system works-they might abandon an identity that has become very valuable to your business. Worse yet, they might abandon your site altogether and take their content with them. (Worst of all, they might take others with them.)

Extreme care must be taken when creating karma systems. There have been many experiments with user reputation on the web to date and the primary lessons can be summed up as: Karma should be a complex reputation and it should be displayed rarely.

Karma is Complex-Built of Indirect Inputs

- Directly rating a user is technically usually too easy to do, and therefore prone to abuse. Combined with the common practice of streamlining user registration processes (on many sites opening a new account is an easier operation than changing your old one's password!) direct evaluation karma models quickly get out of hand. See the example of Orkut in Chap_8-Display_Numbered_Levels .

- Asking people to directly evaluate others is socially awkward. Do you really want to put your honest users in the position of lying about their friends?

- Using multiple inputs presents a broader picture of the target user's worth in the context.

- Economics research into revealed preference or “what people actually do, not just what they say” indicates that actions provide a more accurate picture of value than do elicited ratings.

Karma calculations are often opaque

- Karma calculations may be opaque because the score is valuable as status, revenue potential, and/or unlocking features.

Display karma sparingly

- Public displayed karma should be rare because, as with content reputation, users are easily confused by many reputations on the same page, or within the same context.

- Public displayed karma should be rare because it can create the wrong incentives for your community. Avoid sorting users by karma. See Chap_8-Leaderboards_Considered_Harmful

- If displayed, karma should be visually distinctive from any nearby content reputation. Yahoo!'s EU Message board displays the poster's karma as a colored medallion where the message is rated with stars. But consider this-the Slashdot.com message board doesn't display the poster's karma to anyone. Even the user's personal karma display is vague: Positive, Good, or Excellent. Originally publicly displayed as a number, over time Slashdot karma has incrementally migrated to become increasingly opaque.

- Public displayed karma should be rare because it isn't expected. When Yahoo! Shopping added Top Reviewer karma to encourage review creation, they displayed a Top Reviewer badge with each review and rushed it out for the Christmas 2006 season. After the New Year had passed, user testing revealed that most users didn't even notice the badges. When they did notice them, many thought they meant either that the item was top rated or that the user was a paid shill for the product manufacturer or Yahoo!.

Karma caveats

Though karma should be complex, it should still be limited to as narrow a context as possible. Don't mix shopping review karma with chess rank. It may sound silly now, but you'd be surprised how many people think they can make a business out of creating an internet-wide trustworthiness karma.

Yahoo! holds reputation for karma scores to a slightly higher standard than content reputation. We are very careful with terminology and labels that we might apply to a person, for several reasons:

- We want to avoid the appearance of ad-hominem attacks between members of our communities. This sets a hostile tone in the community that others will respond to and amplify. This can be true true whether the label is an overly-positive one (eg. problems with 'Hotshot' or 'Top' designations) or an overly negative one (eg. 'Newbie' or 'Rookie' designations.)

- Sometimes, there are legal reasons: we avoid the term 'Expert' to avoid undue liability. Can you imagine if Yahoo! 'validated' community members by labeling them as experts in a Health Forum and these 'experts' then proceeded to hand out bad advice?

As with all rules of thumb like these, there are contexts where one or more of the points above do not apply. Specifically, role playing games are an example of publicly shared simple karma in the form of experience levels where the context is inherently competitive.

Reputation Display Data

There are numerous options for formatting the display of reputation. We'll discuss only a handful of these (the ones most commonly displayed on the Web.) At this stage in designing your reputation system, in fact, you've already done much of the work of selecting an appropriate pattern for displaying reputation, but look to this chapter for some pros and cons for each format.

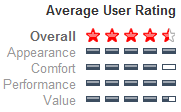

The formats you select for displaying reputation will depend heavily on the types of inputs that you selected in Chapter_7 . If, for instance, you've opted to let users make explicit judgements about a content item with 5-star ratings, then it stands to reason that you would probably display those ratings back to the community using a similar format.

This may not always be the case, however. Many displayed reputations are actually aggregations and transformations of scores derived from very different input methods. For instance, Yahoo! Movies provides a Critics Score as a letter grade compiled from scores from many professional critics, each of whom use a different scale (some use 4- or 5-star ratings, some Up and Down Thumbs, and still others use customized iconic scores.) These all are transformed into normalized scores which we can then display in any form that is convenient.

Before talking about specific display patterns, here is a summary of the four primary classes of reputation data to be considered for display:

- Normalized Score

- Most composite reputations are represented as decimal numbers from 0.0 to 1.0, and all inputs to it were converted, or normalized, to this range. See Chapter_7 for more on the specific normalization functions. Displaying the reputation in the various forms presented here, and others you may discover, is also known as de-normalization: the process of converting it back to a more simplified presentation.

- Summary Count, Raw Score, and other Transitional Values

- Sometimes it is important for a reputation to hold other numeric values to better represent the meaning of the normalized score when it is displayed. For example, a simple-mean reputation also keeps the summary count of the inputs that have contributed to it so that display patterns can make a choice to override or modify the score based on, for example, requiring a minimum number of inputs. See: On Low Liquidity Averages, in Chapter_4 . Sometimes the original input value, or raw score, is kept as well in cases where the normalization process might lose information. Other related or transitional values may be available for display as well, depending on the reputation statement type.

- Free-form Content

- These are free-form inputs, provided by users. They may be constrained along certain dimensions (format, or length, for instance) but are otherwise completely open to the expression of the contributing user. Some examples of this element are User Comments, or Video Responses. Note that things like the Title of a product review (if the review writer is given the option to provide one) should also be considered a Free-form element: it is the review writers opportunity to provide unsolicited, opinionated information about a target. The ability to 'tag' content is also a type of Free-form Content element.

These elements are notable because-while it may be harder to mathematically derive computable values from them (it's not quite as easy as merely tallying votes and reflecting them back) users themselves derive a lot of qualitative benefit from Free-form content.

At Yahoo! study after study has shown us that when reading reviews from other community members (be it for products, albums or movies) it is the body of the review that users pay the most attention to. Not the stars, or number of favorable votes. These matter, but people trust others' words first and foremost. They want to trust an opinion based on shared affinity with the writer, or how well they express themselves. Only then will they pay heed to the other stuff.

- Meta Data

- Sometimes the machine understood information about an object can yield insight into its overall quality or standing within the community. For comparative purposes, you might want to know which of two different videos was available first on your site for instance. Examples of reputation-relevant meta data might include:

- Time stamp

- Geographical coordinates

- Format information, such as the length of audio/video/file

- Number of links to this item or number of times it's been embedded on another site

Reputation Display Patterns

Normalized Score ? Percentage

A normalized score ranges from 0.0 to 1.0 and represents a reputation that can be compared to other reputations no matter what forms were used for input. When displaying normalized scores to users, it is recommended to convert it to a percentage (multiply by 100.0) - the numeric form most widely understood around the world. From here on, when talking about displaying a percentage or normalized score to users, this transformation should be assumed.

The percentage may be displayed as a whole number, or with fixed decimal places depending on the statistical significance of your reputation as well as user interface and layout considerations. Remember to always include the percentage mark (%) in order to prevent any confusion with either Points or Numbered Levels display.

Use:

- When the normalized reputation score is reasonably precise and accurate. For example if there have been hundreds or thousands of votes in an election, displaying the exact average percentage of affirmative and negative votes is easier to understand than the just showing total votes cast for and against.

- Consider a graphical sliding-scale or thermometer view to represent a normalized score as it can make some simple reputations easier to understand at a glance. If needed, also display the numeric value alongside the graphic.

- When the input scale isn't suitable for normalized output of the aggregated results. For example, consider the displaying the results of a series of Up/Down Thumb ratings; Though you can display the Thumb graphic that got the majority of votes, you'll probably still want to display either the raw votes for each or the percentage the total each for of Up and Down Votes as well.

Normalized Score ? Percentage

- Figure_8-4 displays content reputation as the percentage of thumbs-up ratings given on Yahoo! Television for a television episode. Note that the simple average calculation required the display of the total number of votes in order for users to evaluate the reliability of the score.

- Figure_8-5 shows multiple of Okefarflung's karma scores as percentage bars, each representing his reputation with various political factions on Worlds of Warcraft. Printed over each bar is one of the current Chap_8-Display_Named_Levels his current reputation falls within.

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Points & Accumulators

Points are a specific example of an accumulator reputation: The score simply increases or decreases in value over time, either monotonically (one at a time) or by arbitrary amounts. Accumulators values are almost always displayed as digits, usually with a units designation shown adjacent, such as 10,000XP or Posts: 1,429. The aggregation of the Vote to Promote input pattern is an accumulator.

If an accumulator has a maximum value that is understood by the reputation system, it can be alternatively displayed using any of the display patterns for normalized scores, such as Percentages and Levels.

Use:

- Publicly display points when you wish to encourage users to take actions increase or decrease the value for this entity.

- Alternatively, consider keeping the points value personal and have any public display be either a Numbered or Named Level.

- When displaying counts of actions collected from many users, such as voting and favoriting.

![]()

Points & Accumulators

- Figure_8-6 shows

- Figure_8-7 displays

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Statistical Evidence

A very useful strategy can be to simply expose as many of the inputs into a content item's reputation as possible, without necessarily attempting to aggregate these into visible scores. We call this Statistical Evidence. It lets users 'key in' on the facets of a piece of content that they consider to be the most telling. These might be a series of simple accumulator scores:

- Number of Views

- Number of Links

- Number of Comments

- Number of Times Favorited or Voted

Use:

- When a variety of data-points would provide a well-rounded view of an entities worth or performance

- When displaying counts of actions collected from many users, such as voting and favoriting.

Statistical Evidence

- Figure_8-8 shows

- Figure_8-9 is

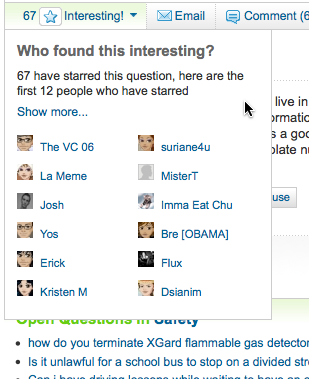

- Optionally, you might extend Statistical Evidence to include even more information about how a particular score was derived. Figure_8-10 shows how Yahoo! Answers displays not only how many people have “starred” a question (found it interesting) but also lets you see exactly who starred it. This can have ill-intended consequences, however. It may create an expectation of social reciprocity (your friends might become upset when you opt not to endorse their contribution, for instance.)

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Levels

Levels are used to display reputation in order to remove insignificant precision from the score. Each level is a bucket holding all the scores in a range. Levels allow you to round-off the results in order to present a simpler display. Note that the range of scores in each level need not be evenly distributed, as long as the users understand the relative difficulty for an entity to reach each level.

Common display patterns for levels include Numbered Levels and Named Levels.

Use:

- If the reputation is an average and inputs are limited to a small, fixed set, such as 5-stars.

- If the reputation is an average and may be calculated from a very small number of inputs. Levels will hide irrelevant precision.

- Your reputation accumulates at a non-linear rate. For example, in many role-playing games each experience level requires twice as many experience points as the previous level.

- There are features of your application that are unlocked based on the reputation score - users will want to know that they've achieved the required threshold.

- Be careful using levels when the input was gathered using a different scale. If the user clicked on Up/Down Thumbs, displaying the resulting score as 5-stars is confusing.

- Be careful when listing entities by level not to surface relative position within a level. This can encourage an undesired competition between for specific page positions. Remember to always sort by the lower precision level value, not the high precision normalized value.

Numbered Levels

This is the most basic level display form and is displayed as a simple numeric value or a repeated list of icons representing the level that the reputation score falls into. Usually levels are 0 or 1 to n, though arbitrary ranges are possible as long as they make sense to the user. It may be an integer or a rounded fraction, such as 3½ stars. If the representation is unfamiliar to the user consider adding a UI element to explain the score and how it was calculated. This requirement is mandatory for reputations that have non-linear advancement rates.

Use:

- If the displayed level will be used to sort a list of entities.

- It the inputs for this reputation were also numbered levels. Input stars? Output Stars.

- If there are more than ten levels being displayed. Consider using numbered instead of named levels if there are more than five.

Numbered Levels

- Figure_8-11 shows

- Figure_8-12 has

- Figure_8-13 displays

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Named Levels

A named level display form substitutes the level number with a short, readable string of characters.

This adds semantic meaning to each level so that users can more easily recognize the entity's reputation when it is displayed separate from entities. Is the user a Silver Contributor or is the beef Prime, Choice, Select, or Standard?

Use

- Consider using this pattern when you have a small number of levels, typically five or less, that you can accurately name to express the meaning of each level.

- If you feel that numeric levels are too impersonal or encourage undesired competition.

- If you'd like your top and bottom levels to feel closer together than the numeric distance between them would otherwise indicate. Especially useful with karma scores so that new participants don't get stuck with a demeaning level indicator.

| Species | Quality Grades |

| Beef | Prime, Choice, Select, Standard, Utility, Cutter, Canner |

| Lamb and Yearling Mutton | Prime, Choice, Good, Utility, Cull |

| Mutton | Choice, Good, Utility, Cull |

| Veal and Calf | Prime, Choice, Good, Standard, Utility |

Named Levels

- Table_8-1 and Figure_8-14 show

- Figure_8-15 displays

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Ranks

Any list based on highest- or lowest- reputations scores. Ranking systems are by their very nature comparative, and-human nature being what it is-are likely to be received by your community as competitive as well.

Leaderboard

A leaderboard is a rank-ordered listing of reputable entities within your community or content-pool. Leaderboards may be displayed in a grid, with rows representing the entities, and columns describing those entities across one or more characteristics (Name, Number of Views, or the like.) Leaderboards provide an easy and approachable way to display the best performers in your community.

Use

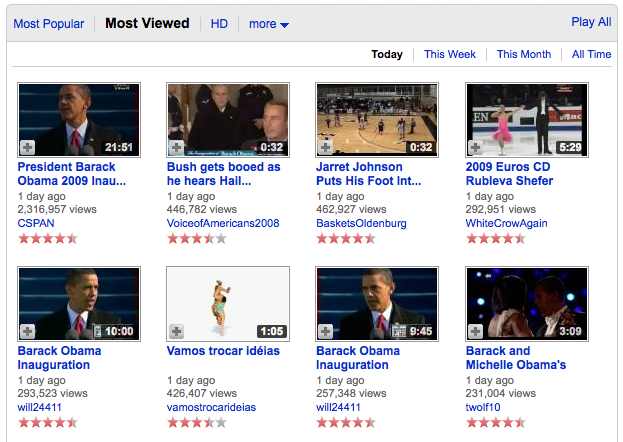

- Use leaderboards for content liberally. Provide filtered views of the boards, to slice-and-dice by time (Popular Today | This Week | All Time) or by reputation-type (Most Viewed | Top-Rated.)

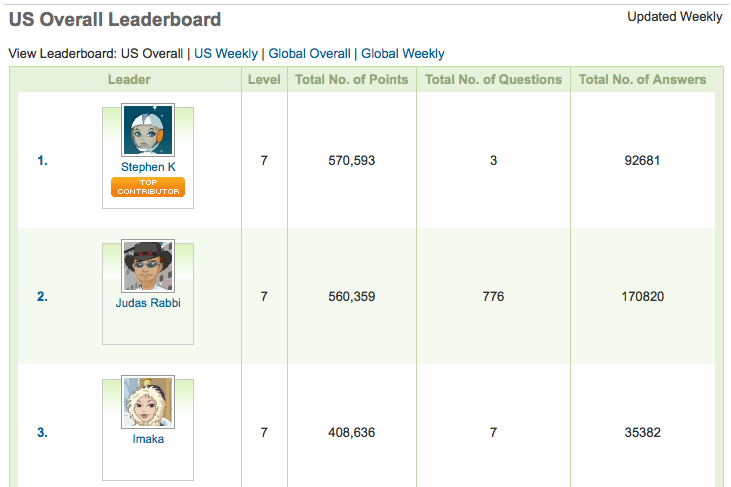

- Use leaderboards for people sparingly, and only in contexts that are competitive by nature. Consider scoping people leaderboards more narrowly (only ranking me against my friends for instance, to keep the comparisons fun and the stakes low.)

Leaderboards

- Figure_8-16 shows

- Figure_8-17 displays

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Top X

A specialized type of leaderboard where top-ranking entities are grouped into numerical categories of performance. Achieving 'Top 10' status (or even Top 100) should be a rare and celebrated feat!

Use

- Use Top X leaderboards for content to highlight only the best-of-the-best of your community's contributions.

- Use Top X designations for people sparingly, and only in contexts that are competitive by nature. Because available categories in a Top X system are bounded, they will have greater perceived value in the community.

Top X

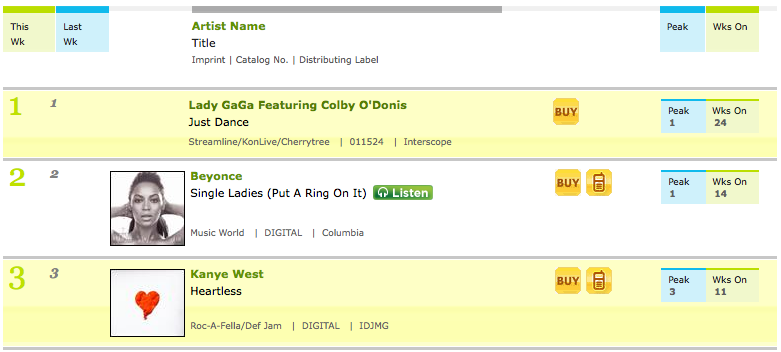

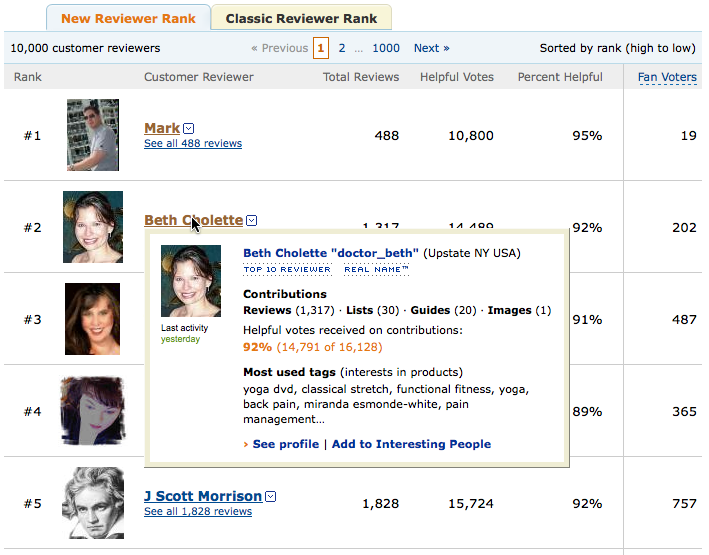

- Figure_8-18 shows

- Figure_8-19 displays

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

Practitioners Tips

Leaderboards Considered Harmful

It's still too early to speak in absolutes about the design of social-media sites, but one fact is becoming abundantly clear: ranking the members of your community – and pitting them one-against-the-other in a competitive fashion – is typically a bad idea. Like the fabled djinni of yore, leaderboards on your site promise riches (comparisons! incentives! user engagement!!) but often lead to undesired consequences.

So why do we use them? The typical thought-process goes something like this: there's an activity on your site that you'd like to promote; a number of people engaged in that activity who should be recognized; and a whole buncha other people who need a kick in the pants to jump in. Leaderboards seem like the perfect solution. Active contributors will get their recognition: placement at the top of the ranks. The also-rans will find incentive: to emulate leaders and climb the boards.

And that activity you're trying to promote? Usage should swell with all those earnest, motivated users plugging away, right? It's the classic win-win-win scenario! In practice, employing this pattern has rarely been this straightforward. Here are but a few reasons why leaderboards are hard to get right.

What do you measure?

Many leaderboards make the mistake of basing standings on only what is easy to measure. Unfortunately, what's easy to measure oftentimes tells you nothing at all about what is good. Leaderboards tend to fare well in very competitive contexts, because there's a convenient correlation between measurability and quality. (It's called “performance” – number of wins versus losses within overall attempts.)

But how do you measure quality in a user-generated video community? Or a site for ratings and reviews? It should have very little to do with the quantities of simple activity that a person generates (the number of times an action is repeated, a comment given or a review posted.) But these types of things – discrete, countable and objective – are exactly what leaderboards excel at.

Whatever you do measure will be taken way too seriously

Even if you succeed in leavening your leaderboard with metrics for quality (perhaps you weigh community votes, or count 'send-to-a-friend' actions), be aware that – because the leaderboard singles these factors out for praise and reward – your community will hold these things in high esteem as well. Leaderboards have this amazing 'Code of Hammurabi' effect on community values: what's written becomes the law of the land. And you'll likely notice this effect in the things that people do – and won't do – on your site. So tread carefully – are you really that much smarter than your community, that you alone should dictate the makeup of its character?

If it looks like a leaderboard, and quacks like a leaderboard...

Even sites that don't display overt leaderboards may veer too closely into the 'comparative statistics' realm. Consider Twitter, and its prominent display of community members' stats.

The problem may not lie with the existence of the stats but - perhaps - in the prominence of their display. They give Twitter the appearance of a community that values popularity and the sheer size of your social network. Is it any wonder, then, that a whole host of community-created leaderboards have sprung up to automate just such comparisons? Twitterholic, Twitterank, Favrd and a whole host of others are the natural extension of this value-by-numbers approach.

Leaderboards are powerful and capricious

In the earliest days of Orkut (Google's also-ran entry into social networking), the property managers featured a fun little widget at the top of the site: a country-counter, showing members' geographical origins. Cute, right? Harmless, certainly. Google had no way of knowing, however, that the entire population of Brazil would make it a point of national pride to push their country to the top of that list! Brazilian blogger Naitze Teng writes: “Communities dedicated to raising the number of Brazilians on Orkut were following the numbers closely, planning gatherings and flash mobs to coincide with the inevitable. When it was reported that Brazilians had outnumbered Americans registered on Orkut, parties […] were thrown in celebration.”

Today, Brazil maintains its number one position on Orkut (51% of Orkut users are Brazilian as of this writing – the US and India are tied for a distant second with 17% apiece.) Orkut is – basically – a Brazilian social network. Which is not a bad “problem” for Google to have, but probably never an outcome they would have expected from such a simple, small and insignificant thing as a leaderboard widget.

Cui bono?

This may be the most insidious artifact of a leaderboard community: the very presence of a leaderboard changes the community dynamic and calls into question the motivations of everyone for any action they might take. If that sounds a bit extreme, consider Twitter: friend counts and followers have become the coins of that realm, and when you get a notification of a new follower…? Aren't you just a little more likely to believe that it's just someone fishing around for a reciprocal 'follow'? Sad, but true. And this is a site that itself has never officially featured a leaderboard. Twitter merely made the statistics known and provided an API to get at them: in doing so, they may have let the genie out of the bottle.

<note>(Leaderboards Considered Harmful first appeared as an essay inDesigning Social Interfacesby Christian Crumlish and Erin Malone from O'Reilly Media and Yahoo! Press and also available online at http://www.designingsocialinterfaces.com/.)

</WRAP>