Table of Contents

Objects, Inputs, Scope, and Mechanism

Moving from Goals to Design

Now it's time to get real. We've asked a bunch of pertinent questions, and tried to marry your responses back to our foundational material in Part 1. By now, you should have a pretty good idea of what you hope to accomplish with your system. In this chapter, we're going to start showing you how to accomplish these goals. We'll actually start identifying the components of your reputation system and systematically determine:

- Which objects in your application will play a part in the reputation system? (Some will themselves be Reputable Entities and accrue and lose reputation over time – others may not directly benefit from having a reputation, but may play a part in the system nevertheless.)

- What are the inputs that will feed into your system? These will frequently take the form of actions that your users may take, but there are other inputs that are possible and we'll discuss these in some detail.

- In the case of user-expressed opinions and actions, what are the appropriate mechanisms to offer your users? Is there a difference between 5-star ratings, Thumbs-up voting and social bookmarking? (Of course there is!)

In addition, we'll share a number of practitioner's tips, as always. This time around, we'll consider the effects of exclusivity on your reputation system (how stingy, or how generous, should you be when doling out reputations?) We'll also provide some guidance for scoping your reputations appropriate to your context.

The Objects in Your System

In order to accomplish your application's reputation-related goals, you'll have two main weapons in your arsenal - the objects that your software understands and the software tools, or mechanisms, to provide to users and other processes to utilize. Simply put, if you want to build birdhouses, you need wood and nails (the objects) along with saws and hammers (the tools) - and someone to do the actual construction (the users).

Architect, Understand Thyself

Where will the objects in your reputation system come from? Why, from your application, of course! So, at this stage, a little bit of clarity about the architecture and makeup of your application would be a good thing.

Parts of this chapter may seem as if we're describing a “brownfield deployment” of your reputation system: assuming that you already have an application in mind (or in production) and are merely retro-fitting a reputation system onto it. This is not at all the case! You would go through the same set of questions and dependencies regardless of whether your host application is already live or is still in the planning stages. (It's just much easier for us to talk about reputation as if there are already some a priori objects and models to graft it onto. Planning your application architecture is a whole other book altogether!)

Think About It

This will be easier than it sounds. You know your application, right? You can probably list off the 5 most important objects that are represented in your system without even breaking a sweat. So a good first step is to do just that. In fact, a decent place to start is with your application's “elevator pitch.” Try to just–succinctly and economically–describe what it is your application does. For instance, you might describe something like the following: - A social site for sharing recipes and keeping and printing shopping lists of ingredients

- A tool for editing music mashups, building playlists of them and sharing those lists between friends

- An intranet app that lets paralegals access and save legal briefs and share them with coworkers

These are pretty short, sweet (and somewhat vague) descriptions of three very different applications, but–already–they tell us much of what we need to know to plan our reputation needs for each. Our recipe-sharing site will likely benefit from some form of reputation for recipes and will require some way for users to rate them. The shopping lists? Not so much–those are more like utilities for individual users to manage the application data.

If an artifact or object within your system has an audience of one, then you probably don't need to display a reputation for it. But you may keep one, as a useful input to roll up into other, more visible objects' reputations.

The music site? Perhaps its not any one individual track that's most interesting–maybe its quality of the playlists that we'd like to assess. Or maybe it's our users' reputation as a deejay (their performance, over time, at building and sustaining an audience) that will be most relevant. (In truth, tracking either of these will probably also require us to keep mashup tracks as an object in the system. But we may not necessarily treat them as first-class reputable entities.)

And our intranet app for paralegals sounds as if the briefs are the primary atomic unit of interest. Who's saved what briefs, how are users adding metadata, and how many people attach themselves to a document? These are all useful bits of information to have and will help us filter and rank briefs to present back to other users.

So this is the first step toward defining the relevant objects in your reputation system: start with what's important in the application, and think forward just a little bit to: what types of problems will reputation help my users solve? Then you're ready to move on…

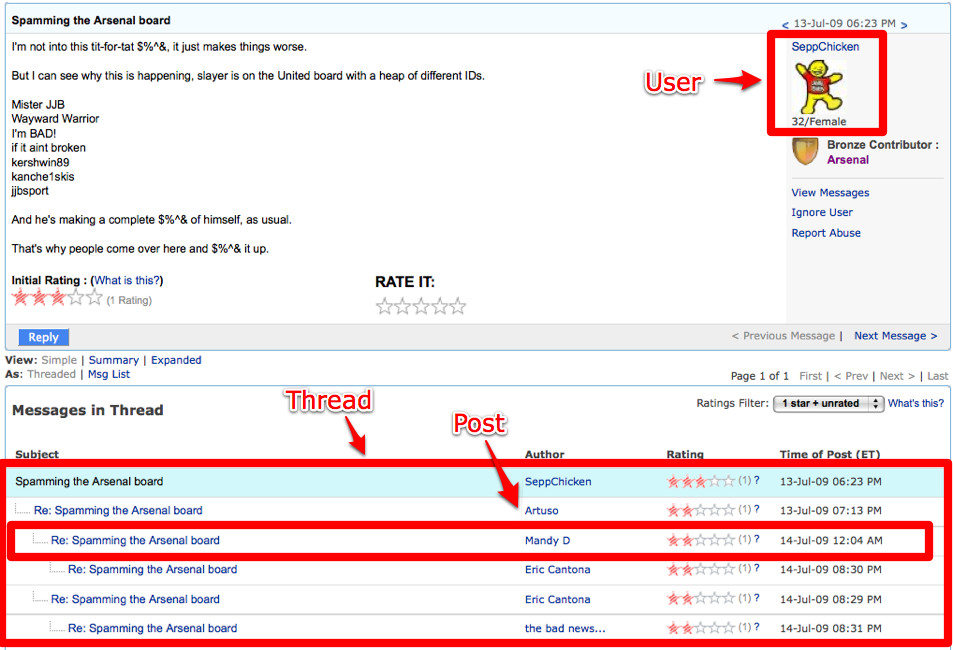

Perform an Application Audit

Although you've thought, at a high level, about the primary objects present in your application, there are probably some smaller-order, secondary objects and concepts that you've overlooked. These primary and secondary objects relate to each other in interesting ways that we can make use of in our reputation system. It may be helpful to do an application audit to fully understand the entities that are present in your application and see how they relate to one another.

Make a complete inventory of every kind of object your application understands that may have anything to do with accomplishing your goals. Some obvious things are user-profile records and the data objects that are special to your application: movies, transactions, landmarks, CDs, cameras, or whatever - these are clear candidates as reputable entities. It is most important to know what objects will be the targets of reputation statements and any new ones you'll need to create for that purpose. Make sure you have a good understanding of the meta-data surrounding that object and how your application can access it. How are they organized? Are they searchable by attributes? Which attributes? How are the different objects related to each other?

Some of the objects in your application will be visually evident and are represented directly in the interface–so you may want to start with a simple screen-based audit. Work from screen designs of your application at whatever fidelity is available. For in-progress projects, early-stage wireframes are fine–if your app is in production, then take some screen snags and print them out on paper.

Be sure to also list items whose creation, editing, or content can be used as input into your reputation model, some common types of items on that list are: categorization systems (folders, albums or collections), tags, comments, uploads, historical and current session information including browser cookies, historical activity data, external reputation information, and special processes that provide application-relevant insight. For an example of on of these processes, consider a dirty-word filter that is applied to user-supplied text messages and replaces positive matches with asterisks (), the real-time results might be a useful hook for measuring the effects of interface changes on this particular user behavior.

What Makes for a Good Reputable Entity?

A good candidate to be tracked as a reputable entity in your system probably has one or more of the following characteristics.

People are interested in it

Duh. I guess this should go without saying, but – what the heck – let's say it anyway. If your entire application offering is built around a specific type of object, social or otherwise, then that's probably a good potential candidate to become a reputable entity. That part should be self-evident.

And remember, nothing interests people more than… other people! This alone is as good an argument for at least considering Karma (people reputation) for any application that you might build. Your users will always want every possible edge in understanding other actors in the community: what motivates them? What actions have they performed in the past? How might they behave in the future?

When considering the objects in your application that will be of the most interest to your users, don't overlook other, related objects that may benefit them as well. For example, on a photo-sharing site, it seems a natural assumption to track a photo's reputation, no? But what about photo albums? They're probably not the very first application object that you'd think of, but there are likely some situations where you'll be more apt to want to direct users' attention to high-quality groupings or collections of photos.

The solution is, you'll want to track both objects in the reputation system. Each may affect the reputation of the other to some degree, but the criteria, the inputs and weightings you'll use to generate reputation for each will–of necessity–vary.

The Decision Investment is High

Some decisions are easy to make. They require very little investment, in terms of time or effort. And the cost to recover from these decisions is negligible. “Should I read this blog entry?” for instance, might be such a decision. If it's a short entry, and I'm already engaged in the act of reading blogs, and there are no other distractions calling me away from that activity, then–yeah–I'll probably go ahead and give it a read. (Of course, the content of the entry itself plays a big factor. If the entry's title or a quick skim of the body don't interest me, then I'll likely pass it up.)

The level of decision investment is important because it affects the likelihood that a user will make use of available reputation information for an item. In general, the greater the investment in a decision, the more a user will expect (and make use of) robust supporting data. So for high-investment decisions (purchasing decisions, or any decision that is not easily-rescinded after the fact) we should offer more-robust mechanisms, like reputation information, for users to make decisions against.

It has some intrinsic value worth enhancing

Regardless of how slick, unobtrusive and accomplished your reputation system is, you're going to be asking alot of your community to accept its obtrusive presence. (Not to mention, you'll need to keep them 'playing along' to FEED the beast.) Reputable entities should have some intrinsic value already.

You should never ask users to provide meta-data (basically 'add value') to an item who's own apparent value is low. Or, more specifically: only ask for user participation in way's that appropriate to an item's intrinsic value. It might be okay to ask someone to give a Thumbs-up rating to someone else's blog-comment (because the 'cost' for them in doing so is low–basically, a click.) But it would be inappropriate to ask for a full-blown review of the comment. There would be more effort and thought involved in writing the review than there was in the initial comment!

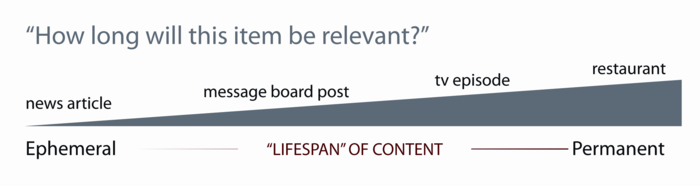

It should persist for some length of time

Reputable entities must remain in the 'community pool' long enough for all members of the community to cast their vote. There's little use in asking for a bunch of meta-data for an item if others cannot come along afterward and enjoy the benefit of that meta-data.

Highly ephemeral items, such as News articles that disappear after 48 or 72 hours, probably aren't good candidates for certain types of reputation inputs. You wouldn't, for instance, ask your users to author a multi-part review of a news story destined to vanish in less than a day. You might, however, ask them to click a 'Digg This' or 'Buzz This' button.

Items with a great deal of persistence (on the extreme end are real-world establishments such as restaurants or businesses) make excellent candidates for reputation–furthermore, the type of inputs we can ask of our users may be more involved. Because these establishments will persist, we can be reasonably sure that others will always come along afterward and benefit from the work that the community has put into them.

Determining Inputs

Now that you've got a firm grasp on your objects, and have elected a handful of those to be reputable entities in your system, you need to decide: how will we decide what's good? And what's bad? What are the inputs that will feed into the system, that we will tabulate and roll up to establish relative reputations amongst like objects?

User actions make for natural inputs

Now, instead of merely listing the objects that a user might interact with in your application, we're going to enumerate all of the possible actions that a user might take against those objects. Again, many of these actions will be obvious and visible ones, right there in your application interface, so let's build upon the audit that you performed earlier for objects. But this time, we'll

Explicit Claims

Explicit claims represent your community's voice and opinion–here, you provide interface elements that solicit your users' opinions about an entity, good or bad. There is a fundamental difference between explicit claims and implicit ones (discussed below) and it all boils down to user intent and comprehension. With explicit claims, users should be fully aware that the action they're performing is intended as an expression of an opinion. This is very different than implicit claims, where a user is mostly just going about their business, but generating valuable reputation information as a side-effect.

Provide a Primary Value

If you present explicit inputs to your users as only that – a mechanism for generating reputation information to feed the system and make your site smarter – then you may be inhibiting the uptake of your community for those features. You will likely see better performance from those inputs if they also provide some primary value to the user. This is a self-evident, and recognizable benefit that the user gets from interacting with the widget (above and beyond just “feeding the system.”) This primary value can be big or small, but it will probably share some of the following characteristics:

- It provides a benefit to the user for interacting with the system. Comments on Digg, for instance, are hidden for a particular user when she 'Diggs (thumbs) them down.' This is immediately useful to the user–it cleans up her display! And makes that thread more readable.

Likewise, 5-star ratings in iTunes are surpassingly useful: not because of any secondary or tertiary 'reputation' benefits they may yield: no, for most iTunes users who rate, those stars are primarily valuable as a well-articulated and extremely flexible data-management mechanism. You can sort your own track listings based on Stars, you can build smart playlists, get recommendations from the iTunes Store. Stars in iTunes are full of Primary Value.

- Its feedback is immediate and evident. Unlike the reputation effects that may happen downstream (which may not be immediately evident to the user) there should be some quick acknowledgment from the system that the user has expressed a claim.

Implicit Claims

Any time a user takes some action against a entity, it is very likely that there is valuable reputation information to be derived from that action. Recall our conversation about implicit and explicit reputation claims in Chap_1-The_Reputation_Statement ? With implicit reputation claims, we are going to watch not what the user says about the quality of an entity. Rather, we are going to watch how they relate to, and interact with, that object. For example, assume a reputable entity in your system is a Text Article. * Do they read it? To completion?

- Save it for later use?

- Bookmark it

- Clip it

- Share it with someone else?

- Send it to a friend

- Publish to their tweet-stream

- Embed it on their blog

- Clone it, to base a like article of their own from?

There are any number of very clever, devious and effective reputation models that you can construct from relevant related action-type claims. Your only real limitation is the level and refinement of instrumentation that your application has: are you prepared to capture relevant actions at the right junctures and generate reputation events to share with the system?

Don't get too clever with these implicit action-type claims. Your community is not stupid! Should you choose to weigh actions like these in the formulation of an object or a person's reputation AND you make that fact know to any degree, then it's likely that you will influence the community's behavior in such a way that you're actually motivating users to take these actions in an arbitrary fashion. This is but one reason that many reputation-intensive sites play somewhat 'coy' with regards to the types and weightings of claims that their system considers.

But there are other types of inputs as well

A reputation system does not exist in a vacuum - it is part of a bigger application which itself is part of a bigger ecosystem of applications. There are many sources of relevant inputs, other than those generated directly by user actions. be sure to build/buy/include these in your model where needed. Some common examples are:

- External trust databases

- Spam IP Blacklist

- Home-brewed text scanning software for dirty words or other abusive pattern

- Reputation from other applications in your ecosystem

- Social Networking Relationships

- May be used to infer positive reputation by proxy

- Relationships should be considered as a primary search criteria when surfacing a friend's evaluation of a reputable object in many cases: “Your brother recommends this camera”.

- Session Data

- Browser Cookies are good for tracking logged out new users

- Session Cookies can be used to build up a reputation history

- Identity Cookies allow the linking of various identities, browsers, and sessions together

- Asynchronous Activations

- Just-in-time inputs - many reputation models are real-time systems where the reputation needs to change constantly even when users aren't providing any direct input. For example, a mail anti-spam reputation model for IP addresses would expect irregular inputs about mail volume received over time from an address to allow the reputation to naturally reflect traffic.

- Time-activated inputs, often called Chron Jobs (for the unix tool

chronwhich executes them) are often used to start a reputation process in order to perform periodic maintenance, such as triggering reputation scores to decay or to expire a time-limited side effect. These timers may be periodic or scheduled ad-hoc by the reputation model itself. - Customer Care corrections and operator overrides - When things go wrong, someone's got to fix it via a special input channel. This is a common reason that many reputation processes are required to be reversible.

Of course, the messages output by each reputation process are also potentially inputs into other processes. Well designed karma models don't usually take direct inputs at all - they are always downstream from other processes that encode the understanding of the relationship between the objects and transform that to a normalized score.

Good Inputs

Whether your system features explicit reputation claims, implicit ones, or a skillful combination of both you should strive to…

- Emphasize indicators of quality, not simple activity. Don't continue to reward people or objects for performing the same action over and over–rather, try to single out those events that indicate that the target of the claim is something worth paying attention to. For instance, an act of someone bookmarking an article is probably a more-significant event than a number of page-views for that article. Why is this? When a user bookmarks something, it is a deliberate act–the user has assessed the object in question and decided that it's worth further action.

- Rate the thing, not the person. Creating karma is subtle more complex and socially delicate than object reputation. For a deeper explanation, see Karma is Complex, Chap_8-Displaying_Karma . At Yahoo!, we always attempted to adhere to a general community policy of only soliciting explicit ratings input about user-created content-and never have users directly rate other users. This is good for a number of reasons:

- It keeps the focus of debate on the quality of the content an author produces (and not on the quality of their character.)

- It reduces ad-hominem attacks and makes for a nicer culture within the community.

- Pick events that are hard for one user to replicate with ease (to combat gaming.) But you should probably anticipate collusion amongst users anyway. Be prepared to spot these patterns of behavior, and leave room in your system to deal with offenders.

- Use the right scale for the job. We talked some in Chap_4-Ratings_Bias_Effects about Ratings Distributions and why you should pay attention to them. If you're seeing data with poorly actionable distributions (basically, data that doesn't tell you much) then it's likely that you're asking for the wrong inputs. Pay attention to the context in which you're asking. For example: if interest in the object being rated is relatively low (perhaps it's “official” feed content from a staid, corporate source) then 5-star ratings are probably overkill. Your users won't have such a wide range of opinions about the content that they'll need five stars.

- Match user expectations. That is, you should try to ask for information in a way that's consistent and appropriate with how you're going to use that information. A really simple example: if your intent is to display the community average rating for a movie as 1-5 stars, then it is perfectly acceptable (expected even) that you would gather that information from users in a matching format: in this case, asking your users to enter a 5-star rating for a movie makes perfect sense to them. You can, of course, do transformations on reputation scores and present them back in ways different than how they were solicited (See Chap_7-What_Comes_In ) but strive to only do this when it makes sense to do so, and in a way that doesn't confuse your users.

Common Explicit Inputs

In Chapter_8 we will focus on displaying aggregated reputation constructed in part with the inputs we discuss here and several of the output formats are identical to those of the inputs. 5-stars in, 5-stars out for example. But that symmetry exists for only a subset of inputs and an ever smaller subset of the aggregated outputs. For example, an individual vote is a Yes or a No, but the result is a percentage of the total votes for each.

In this chapter, we're discussing only claims at the input side - what does the user see when he takes an action that is sent into the reputation model and is transformed into a claim? What, if anything, does the user see when they see their input reflected back to them?

What follows are a set of best practices for the common explicit input types and our best practices for their use and deployment. The user experience implications of these patterns are also covered to more depth in Designing Social Interfaces (O'Reilly).

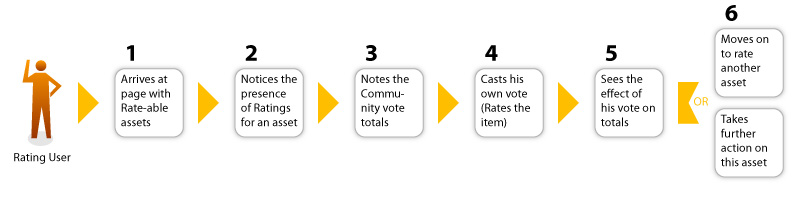

The Ratings Lifecycle

Before discussing all of the ways that users might provide explicit feedback about objects in our system, it might be useful to think, for a moment, about the context surrounding these actions. Remember, our perspective (in this book) is organized around users generating reputation information – usable meta-data about objects and other people. But our users' focus is another matter altogether–see Figure_7-5 . Feeding our reputation system is likely the last thing on their mind.

Given the other priorities, goals and actions that your users might possibly be focusing on at any given point during their interaction with your application, here are some good general guidelines for increasing the efficacy with which you gather explicit reputation inputs.

Visual Design

Your application's interface design can reinforce the presence of input mechanisms in several ways: * Input mechanisms should be placed in comfortable and clear proximity to the target object that they modify. Don't expect users to find a ratings widget for that television episode when it's buried at the bottom of the page! (Or, at least, don't expect them to remember which episode it applies to… or why they should click it… or…

- Accordingly, don't intermix too many different rate-able entities on a single screen. You may have perfectly compelling reasons to want users to rate a product, a manufacturer and a merchant all from the same page – just don't expect them to do so consistently and without confusion on their part.

- Strike a careful balance between the size and proportion of reputation-related mechanisms and any other (perhaps more-important) actions that might apply to a reputable object. For example, in a shopping context, it is probably appropriate to keep 'Add to Cart' for an item as the predominant call-to-action, with 'Rate This' being less noticeable. Probably even much less noticeable.

- Stay consistent with the presentation and formatting of your input mechanisms. You may be tempted to try 'fun' variations like… changing the color of your ratings stars in different product categories. Or swapping in little Santa for your thumbs up and down icons for the holidays. In a word: don't. Your users will have enough work in finding, learning, and coming to appreciate the benefits of interacting with your reputation inputs. Don't throw unnecessary variations in front of them.

Stars, Bars and Letter Grades

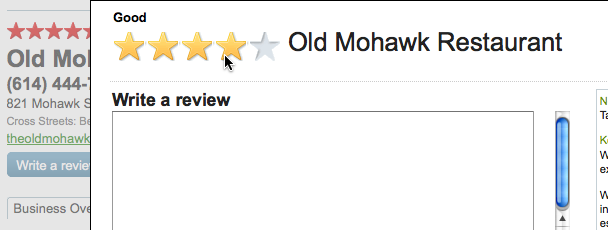

There are a number of different input mechanisms designed to let users express an opinion about an object, across a possible range of values. A very typical one of these Star Ratings (usually a scale of 1-5 though other scales are appropriate in different contexts.) Yahoo! Local (See Figure_7-6 ) allows users to rate business establishments between 1 and 5 stars.

Other input patterns work off of the same mechanism, but are presented

Stars seem like a pretty straightforward mechanism, both for your users to consume (5 star ratings are all over the place, right? they can leverage prior learning) and for you, the system designer, to plan. Tread carefully, though–there are some small behavioral and interaction 'gotchas' that you should think about now, in the design phase.

Stars' Schizophrenic Nature

Star ratings are often displayed back to your users in a format very similar to the one in which they're gathered from your users. This not always need be the case (See Chap_7-What_Comes_In ) but it's usually what is most clear to users. (See Chap_7-Match_User_Expectations .)

This can be problematic for the interface designer, because the temptation is strong to design one comprehensive widget that accomplishes both: displaying the current community average rating for an object and accepting user input to cast their own vote. Slick mouseover effects to change the state of the widget, or 'toggle switches' that do the same are some attempts that we've seen, but this is tricky to pull off, and almost never done well – you'll either end up with a widget that does a poor job at displaying the community average, or one that doesn't present a very strong call-to-action.

The solution that's most typically employed at Yahoo! is to separate these two functions into two entirely different widgets and present them side-by-side on the page. They're even consistently color-coded to keep their intended uses straight. On Yahoo!, red stars are typically read-only (you can't interact with them) and always reflect the community average rating for an entity, while yellow stars reflect your rating (or, alternately, empty yellow stars wait eagerly to accept your rating.) From a design standpoint, it does introduce additional interactive and visual 'weight' to any component that houses ratings, but the increase in clarity more than offsets the extra clutter.

Do I Like You, or do I 'Like' Like You?

Though it's a fairly trivial task to determine numerical values for selections along a 5-point scale, there's no widespread agreement amongst your users on the subjective interpretations of what star-ratings represent. Each user will bring his or her own subtly different interpretation (complete with biases) to the table. Ask yourself the following questions, because your users will have to, each and every time they approach your ratings system:

- What does “one star” mean on our scale? Should it express: Strong Dislike? Apathy? Mild 'Like'? Many Star ratings widgets provide 'suggested' interpretations at each point along the spectrum, like 'Dislike It', 'Like It', 'Love It' and the like. The drawback to this approach it that you're somewhat-constraining the uses that individuals might find for the star-ratings system. The advantage is that the community interpretation of the scale should be in greater agreement.

- What opinion does 'no rating' express? And, should I provide an explicit option for that? Yahoo! Music's 5-star ratings widget feeds a recommender system, designed to suggest new music to you based on what you've liked in the past. They actually offer a 6th option (not presented as a star) intended to express 'Don't Play This Track Again.'

- Is there any way to change my rating? (Again, this is an appeal to keep the interaction difference between rating something and reviewing the community average different and distinct. Changing an already-cast vote is yet another use-case to lade onto an already-overburdened combined mechanism.)

- Can I express half- stars? Quite often, whether or not you permit 1/2-step input for ratings, you will want to permit 1/2-step display of community averages. In any event, note that the possibility of half-values for stars effectivly doubles the expressive range of the scale.

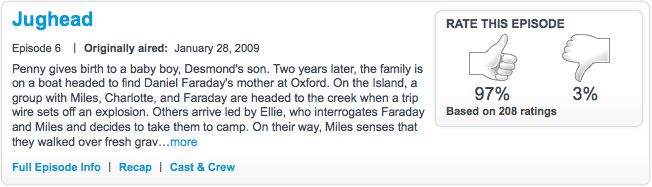

2-state Votes (Thumbs Up/Down)

“Thumb” Ratings provide the ability for a user to, in a fun, engaging fashion, provide a quick rating of a piece of content. The benefit to the rating user is primarily one of self-expression (“I love this!” or “I hate this!”) Of course, the actual visual presentation need not be 'Thumbs', but we'll refer them thusly as an easy kind of shorthand for this type of voting mechanism.

Thumb-ratings allow users to express strongly-polarized opinions about assets. For example, if you can state the question as simply as “Did you like this, or did you not?” then thumbs may be appropriate. If it seems more natural to state the question as “How much did you like this?” then Star-ratings are probably appropriate.

A popular and effective use for 2-State voting mechanisms is as a meta-moderation device for user-submitted opinions, comments and reviews. Wherever you're soliciting user opinion about an object, you may also want to consider letting the community voice their opinion about that opinion: provide an easy control to state 'Was This Helpful?' or 'Do You Agree?'

Avoid thumbs for rating multiple facets of an entity. For example, don't provide multiple thumbs widgets for a product review intended to register a user's satisfaction with that product's Price, Quality, Design and Features. Generally, thumbs should be associated with an object in a one-to-one relationship: one entity gets one thumb up or down. After all, Emperor Nero would never let a gladiator's arm survive, but put his leg to death! Think of thumbs as “all or nothing.”

Consider thumb ratings when a fun, lightweight ratings mechanism is desired. The context for these ratings should be appropriately fun and light-hearted as well. Therefore, don't use thumbs in contexts where they will appear as insensitive or inappropriate. This might include: rating other people; or usages in locales where the thumb imagery itself might be insulting.

In fact, there are several compelling reasons to avoid thumb iconography in your application or site. Not the least of these is the fact that an upraised thumb is considered offensive in some cultures. If your site has potential international appeal, then watch out!

Don't use thumb ratings when you want to provide qualitative data comparisons between assets. For example, in a long listing of movies available for rental, you may want to permit sorting of the list by average rating. If you have been collecting thumb ratings, this sort would have very little practical utility for the user. (Instead, perhaps you should consider a scalar, 5-star- rating style.)

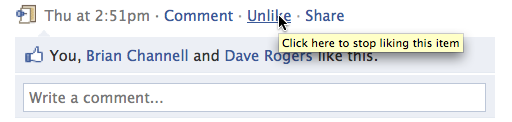

Vote to Promote: Digging, 'Liking' & Endorsing

This is a very simple & oddly satisfying input pattern. As users browse a collection or 'pool' of media objects, give them a control to 'mark' something as worthwhile with a simple gesture. This pattern has been popularized by social news sites such as Digg, Reddit or Newsvine.

There is a related, but different, pattern that leans more toward the implicit school of gathering inputs (See Chap_7-FavoritingForwardingAdding .) They work in very similar ways but, again, the difference lies in user intent. In a Vote-to-Promote system, users are actively marking items with the intention of promoting them to the community (versus storing something for later reference, or passing along to others.)

Typically, this information is used to change the rank-order of items in the pool and present 'winners' with more prominence or a higher stature, but this need not be the case. Facebook offers a 'Like this' button (Figure_7-9 ) simply to do that–communicate your pleasure with an item.

Users who like an item are displayed back to other users that encounter it (and, when the list of vote-casters becomes cumbersome, it is displayed as a sort of summary score) but highly-liked items aren't promoted above other items in the News Feed in any obvious or overt way.

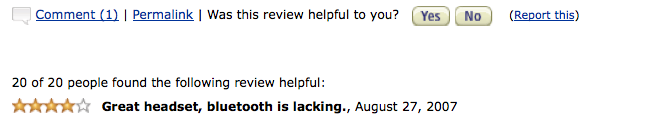

User Reviews

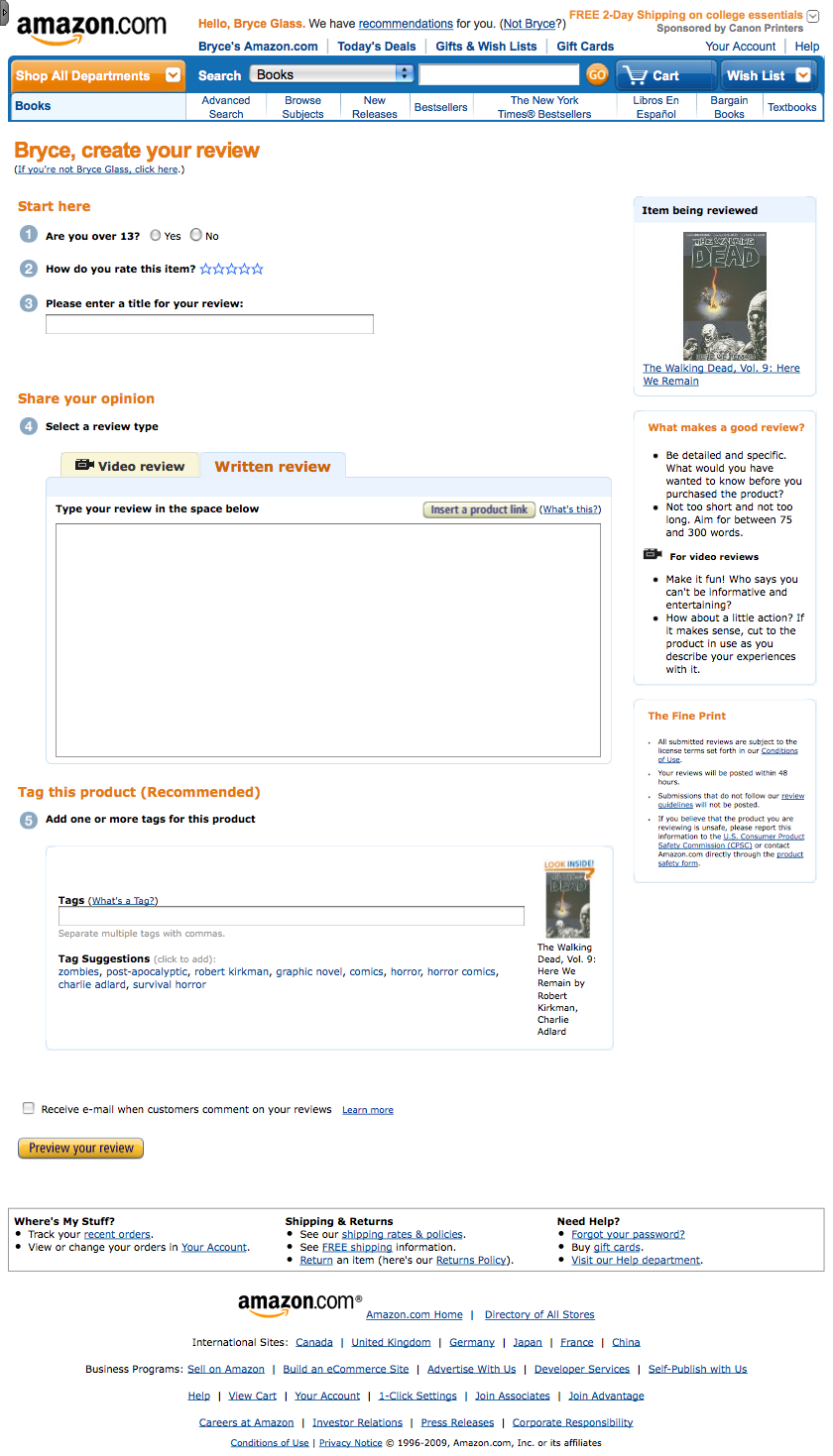

Writing reviews asks a lot of our users. They are amongst the most involved explicit input mechanisms that we can present to them, and usually consist of detailed, multi-part data entry (See Figure_7-10 ). So, to get good usable comparison data back out of user reviews, try to ensure that the objects you offer up for review meet all of the criteria we listed above for good reputable entities. (See Chap_7-Good_Reputable_Entities .) You should only ask users to write reviews for objects that are valuable, long-lived and have high decision-investment cost.

Reviews are typically compound reputation claims: formed from a number of smaller inputs and 'bundled' together in the system as a review. You might consider any combination of the following for your user-generated reviews: * A free-form comment field (see Chap_4-Text_Comments ) where users provide their impressions of the rated object, good or bad. You may exert some standards for content upon this field (eg. checking for profanity, or requiring a certain character-range for length) but generally this is the user's space to do with as they will.

- Optionally, the review may feature a title. Again, free-form, and provides the user an opportunity to 'brand ' their review, or give it some appeal and pizzazz. Quite often, users will use the title field to grab attention and summarize the tone and overall opinion of the full review.

- An explicit, scalar ratings widget, like a 5-Star scale (Chap_7-Stars_Bars_Letter_Grades ). There should almost always be one overall rating for the object in question. So even if you're asking users to rate multiple facets of, say a movie (maybe its Directing, Acting, Plot and Effects) don't forget to provide one prominent rating input for the users Overall opinion. (Yes, you could just derive this average from a combination of the facet-reviews, but that's hardly satisfying for your opinionated reviewer, right?)

- You may want to allow users to 'attach' addition media to a review. Perhaps upload a video testimonial, or attach URLs to additional resources (Flickr photos, or relevant blog entries.) The more participation you can solicit from reviewers, the better. And each of these additional resources might be considered as inputs to bootstrap a review's quality reputation.

Common Implicit Inputs

Remember – with implicit reputation inputs, we are going to pay attention to some subtle and non-obvious indicators in our interface. Actions that – when users take them – may indicate a higher level of interest (indicative of higher quality) in the object targeted.

It is difficult to generalize about implicit inputs because they are highly contextual, and depend on the particulars of your application: its object model, interaction styles and screen designs. But, to give you a sense for the types of inputs you could be tracking, we present the following…

Favoriting, Forwarding, Adding to a Collection

Any time a user saves an object or marks it for future consideration – either by himself, or to pass along to someone else – this might be a reputable event. This type of input shares a lot in common with the explicit input Vote-to-Promote (see Chap_7-Vote_To_Promote ) but the difference lies in user perception: in a vote-to-promote system, the primary motivator for marking something as worthwhile is to publicly state a preference, and the expectation is that information will be shared with the community. It is a more extrinsic motivation. This type of reputation input is more intrinsically-motivated. These actions are taken for largely private purposes:

Favorites

A user 'marks' an item in some easy way (usually, clicking an icon or a link) and adds it to a list of like items that he or she can return to for later browsing, reading or viewing. There is some confusing overlap with 'Liking' an object because – quite often – user favorites might be displayed back to community as part of that person's profile information. It's really just a semantic difference: public 'Liking' or semi-public 'Favoriting' – both can be tallied and feed in almost identical ways into an objects quality reputation.

Forwarding

You might know this as 'Send to a Friend'. This is a largely private communication between two friends, where one passes a reputable entity on to another for review. Yahoo! News has long promoted 'Most Emailed' articles as a type of currency-of-interest proxy reputation. (See Figure_7-11 .)

Greater Disclosure

This is one of those highly-variable inputs, in terms of the range of possibilities for how it might be presented in the interface (and weighted in the reputation processes), but if users are requesting 'More Information' about an object you might consider that as a measure of the interest in that object. This is especially true if they're doing so after having already evaluated some small component of that object: an excerpt, a thumbnail or a teaser.

A common format for blogs, for instance, is to present a menu of blog-entries, with excerpts for each, and a 'Read More' link. A qualified click on one of those links is probably a decent indicator of interest in the destination article. Beware, however – sometimes limitations of presentation in your UI might make functionality like this a misleading indicator. In Figure_7-12 , there may not be enough content revealed to really determine interest level. (Weight this input accordingly.)

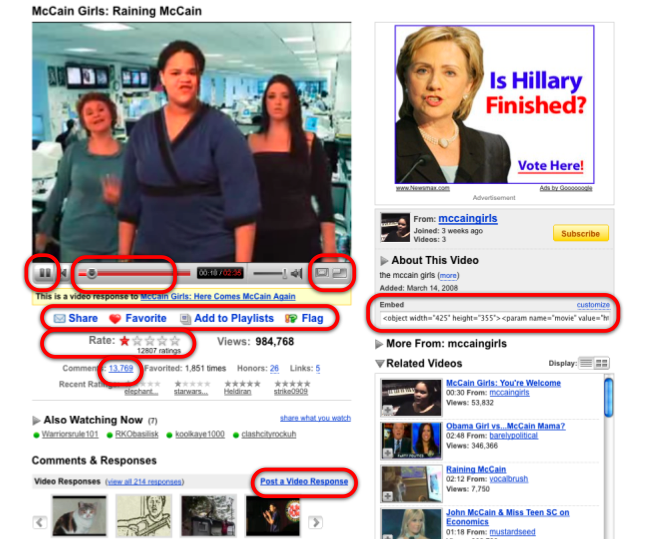

Reactions: Comments, Photos, and Media

One of the very best indicators of interest in an entity is the amount of conversation, rebuttal and response that it generates. While we've cautioned against solely using activity as a reputation input (to the detriment of good quality indicators) we certainly don't want to imply that conversational activity has no place in your system. Far from it! If conversation is happening around an item, then it should benefit from that interest.

Some popular web sites realize the value of rebuttal mechanisms and have formalized the ability to 'attach' a response of your own to a reputable entity. YouTube's 'Video Responses' (see Figure_7-13 ) is such an example. As with any implicit input, however, be cautious – the more evident and upfront your site's design is about how those associations are used, the greater the likelihood that bad actors in the community will mis-use them.

Constraining Scope

When considering all of the objects that you will be interacting with, and all of the interactions between them and your users, it's critical to reiterate an idea that we have been reinforcing throughout this book: all reputation exists within a limited context, which is always specific to your audience and application. Try to determine the correct scope (restrictive context) for your reputations. Resist the temptation to lump all of your reputation generating interactions into just one score and thereby diluting it's value to meaninglessness. An illustrative example from Yahoo! makes our point perfectly:

Context is King

Though this story is specifically about Yahoo! Sports attempting to better integrate social media into their top-tier website, even seasoned product managers and designers can fall in to the trap of assuming the scope of their objects and interactions is much broader than it should be.

The product managers had the appropriate insight that they had to quickly integrate user generated contentacross the entire site.

They had sports news articles, and they knew a lot about what was in each article: the recognized team names, sport names, player names, cities, countries, and other important game-specific terms - the objects-. They new that users liked to respond to the articles by leaving text comments - the inputs-.

They proposed an obvious intersection of these objects and the inputs: Every comment on a news article is a blog post, tagged with the keywords from the article, and optionally by user-generated tags as well. Whenever a tag appeared on another page, such as a different article mentioning the same city, the user's comment on the other article could appear. Likewise, the same comment would appear on the team and player-detail pages for each tag attached to the comment. They even had aspirations to surface them on the sports portal, not just for the specific sport, but for all sports.

Seems very social, clever, and efficient, right?

No. It's a horrible design mistake. Consider this detailed example from British Football:

There's an article stating that a prominent player: Mike Brolly, who plays for Chelsea was injured and may not be able to play in an upcoming championship football match with Manchester United. Users would comment on the article, and they would be tagged with Manchester United, Chelsea, and Brolly and those comments would be surfaced news-feed style on the article page, the sports home page, the football home page, the team pages, and the player page. One post - six destination pages, each a different context.

Nearly all these contexts are wrong, and the correct contexts aren't even considered:

- There is no all Yahoo! Sports community context. American tennis fans don't care. Surfacing it on the home page to them is spam.

- The team pages are a context error because the fans don't mix. The opposing fans have opposite reactions, in this example to the injury of a star player for one side in an upcoming match.

- Have you ever seen a European football game? Where do they keep the fans for each team? On opposite sides of the field - with a chain link fence dividing the field in half - with billy-club wielding police alongside. This is to keep the fan communities apart! Do you really want to encourage the mixing of Chelsea fan reaction to this article with the Manchester United fans? Of course not. So you can't cross post the comment - it'd be out of context.

- The player page may, or may not, be relevant depending on if the user actually responded to the article in the player-centric context - something this design didn't account for knowing.

- The final context - that of the article itself is actually a poor context as well, at least on Yahoo! - since the deal they have with the news feed companies, such as AP and Reuters limits the amount of time an article may appear on the site to less than 10 days! Attaching comments (and reputation) to transient objects such as these tells users that their contributions don't matter in the long run. Sure! Post something, and watch it's context disappear forever tomorrow.

Comments, like reputation statements are created in a context. In the case of comments the context is a specific target audience for the message. Here are some possible correct contexts for cross-posting comments like these:

- a specific fan or team page that was specified by the user - with a sticky preference based on personalization.

- the user's personal blog or “email to a friend” - for when the user knows the context better than you can suggest.

- a well understood related context. For example, Yahoo! Sports has a completely different context that is deeply relevant: A Fantasy Football league, where 12-16 people are building their own virtual teams out of player-entities based on real-player stats. The interesting thing about this context is that the Terms of Service for how these people interact is so much more lax than for public facing posts. These guys swear and taunt and harass each other. In the given example, the comment would be “Ha, Chris - you and the Bay City Bombers are gonna suck my teams dust tomorrow while Brolly is home sobbing to his mommy!”. Clearly the postings for this context can not be assumed to be automatically cross-posted to the main portal page.

Limit Scope: The Rule of Email

When thinking about your objects and user-generated inputs and how to combine them, remember the rule of email:

You need a Subject: line and a To: line for your user generated content.

In this case, the tags act as Subject: identifiers, but not as addressees. Make your addressees as explicit as possible, it will encourage people to participate in many different ways.

Sharing content too widely discourages contributions and dilutes content quality and value.

Applying Scope to Yahoo! EuroSport Message Board Reputation

When Yahoo! EuroSport, based in the UK wanted to revise it's message board system to provide feedback about which discussions and thoughts were the highest quality, as well as to provide incentives for users to contribute better content, more often, they turned for help to reputation systems.

It was clear that there were different scopes of reputation for each post and for all the posts in a thread and, like the American team initially assumed there would be one posting Karma for each user: other users would flag the quality of a post and that would roll-up to their all-sports-message-boards user reputation.

After quickly bringing them up-to-speed on the context issues raised in the previous section, they realized that having Chelsea fans rate the posts of Manchester fans was folly: They'd be using ratings to disagree with any comment by a fan of another team and not honestly evaluate the quality of the posting.

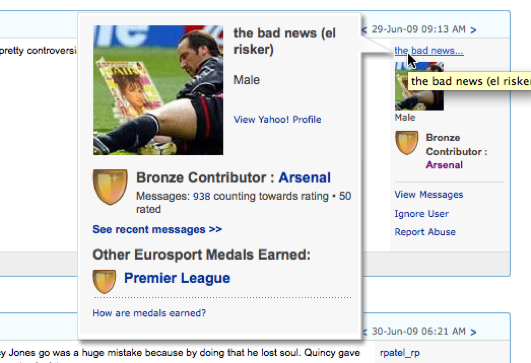

They implemented a system of Karma medallions (none, bronze, silver, and gold) rewarding both the quantity and quality of a user's participation on a per-board basis. In the case of football, each team has a board, so the user can have a medal. The Tennis and Formula 1 car racing topics only have one message board each, so each only has a single set.

Many users have only a single medallion, participating mostly on a single board, but there are those who are disciplined and friendly enough to have bronze badges or better in each of multiple boards, and each is displayed in a little trophy case when you mouse over their avatar or examine at their profile. See Figure_7-14 .

Generating Reputation - Selecting the Right Mechanisms

So, you've established your goals, listed your objects, categorized your inputs, and taken care to group them into appropriate contextualized scopes. Now you're ready to combine these to create the reputations you will use in your application to help you reach those goals.

Though it might be tempting to jump straight to considering how your new reputations will appear to users, we're going to delay that portion of the discussion until Chapter_8 , where we will dig into the reasons you may find that you don't explicitly display some of your most valuable reputations. Instead on focusing on presentation, we're going to take a goal-centered approach.

The Heart of the Machine: Reputation Does Not Stand Alone

Probably the most important thing to remember when you're thinking of how to generate your reputations is the context in which they will be utilized: your applications. If you're planning on tracking bad-user behavior, the purpose might be to save money in your customer care flow by prioritizing the worst cases for quick review and deemphasising those users who are otherwise strong contributors to your bottom line. Likewise, if you're having users evaluate your products and services with ratings and reviews, you will be building significant machinery to gather the user's claims and transform your application's output based on their aggregated opinions.

For the coding required for every reputation score you generate and display or use, expect at least 10x as much development effort to adapt your product to accommodate it - the user interface and coding to gather the events and transform them into reputation inputs as well as all of the locations that will be influenced by the aggregated results.

Common Reputation Generation Mechanisms/Patterns

Though all reputation generation is from a custom built models, there are certain common patterns that we have identified in our experience designing these systems, and from observing those created by others. These few categories are not at all comprehensive - they never could be - they are just meant to provide a familiar starting point for those who applications are similar to well established patterns. We outline them here and will expand on each for the remainder of this chapter.

What Comes In is not What Goes Out

Don't confuse the input types with the generation patterns - What Comes In is not always What Goes Out. In our example Chap_5-User_Reviews_with_Karma the inputs were reviews and helpful votes, but one of the generated reputation outputs was a user quality karma score -which has no display symmetry with the inputs - since no user was asked to evaluate another user directly.

Rollups are often of a completely different claim type then their component parts and sometimes, as with karma calculations, the target object of the reputation changes drastically from the evaluator's original target: The author, a user-object, of the movie review gets some reputation from a helpful score given to the review they wrote about the movie-object.

This section will focus on calculating reputation, and as such these patterns will not include a description of the methods used to display any user's inputs back to the user. Typically the decision to store and reflect the user's action to them is a function of the application design - for example, users don't usually get access to a log of all of their clicks through a site, even if some of them are used in a reputation system. On the other hand, heavyweight operations, such as user-created reviews with multiple ratings and text fields are normally at least readable by the creator, and often editable and/or deletable.

Generating Personalization Reputation

The personalization incentive (See Chap_6-Fulfillment is often the initial driver for may users to provide input to a system - if you tell the model what your favorite music is, the application can customize your internet radio station. So it is worth the effort to teach it my preferences. This provides a wonderful side effect, it provides voluminous and accurate input into Aggregated Community Ratings, which we will cover next.

Personalization rollups are stored per-user and are generally preference information and are not shared publicly. Often these reputations are attached to very fine-grained contexts derived from meta-data attached to the input targets and therefore can be surfaced, in aggregate, to the public. For example, a song by the Foo Fighters may be listed as being in the Alternative and Rock music categories and if a user favorited it the system would increase the personalization reputation for each of Foo Fighters, Alternative, and Rock for this user. Personalization reputation can take a large amount of storage, so plan accordingly, but is well worth the investment.

|

Reputation Models |

Vote to Promote, Favoriting, Flagging, Simple Ratings, etc. |

|

Inputs |

Scalar |

|

Processes |

Counters, Accumulators |

|

Common uses |

Site personalization and display Input to predictive modeling Personalized search ranking component |

|

Pros |

Just asking for a single click is as low-effort as user generated content gets, computation is trivial and speedy. These inputs, intended for personalization, can be re-utilized for generating aggregated community ratings for non-personalized discovery of content. |

|

Cons |

Bootstrapping - it takes quite a few user inputs before personalization starts working properly and until then the application experience can be unsatisfactory. One method for bootstrapping is to create templates of typical user profiles and ask the user to select one to auto-populate a short list of targeted popular objects to quickly rate. Data storage can be problematic - potentially keeping a score for every target and category per-user is very powerful but also very data intensive. |

Generating Aggregated Community Ratings

Aggregated Community Ratings is the process of collecting normalized numerical ratings from multiple sources and merging them into a single score, often an average or a percentage of total.

|

Reputation Models |

Vote to Promote, Favoriting, Flagging, Simple Ratings, etc. |

|

Inputs |

Quantitative - Normalized, Scalar |

|

Processes |

Counters, Averages and Ratios |

|

Common uses |

Aggregated rating display Search ranking component Quality ranking for moderation |

|

Pros |

Just asking for a single click is as low-effort as user generated content gets. Computation is trivial and speedy |

|

Cons |

Too many targets can cause low liquidity. Low liquidity limits accuracy and value of the aggregate score (See Chap_4-Low_Liqudity_Effects ) Danger of using the wrong scalar model (See Chap_4-Bias_Freshness_and_Decay |

There is a specific form of aggregate community ratings that requires special mechanisms to get useful results: When an application needs to completely rank a large dataset of objects and can only expect a small number of evaluations from users. On example is ranking the current year's players in each of the sports league for the annual fantasy sports draft. There are hundreds of players and there is no reasonable way that each user could evaluate each pair against each other - even rating a pair a second it would take many times longer than the available time before the draft. Likewise, there are contests where thousands of users submit content for community-judged contests. Again, comprehensive pairwise comparisons not feasible for any single user. Letting users rate randomly selected objects on a percentage or star-scale doesn't help at all. (See Chap_4-Bias_Freshness_and_Decay )

This kind of ranking is called Preference Ordering. Online this process has users evaluate successively generated pairs of objects and choose from each the most appropriate one. Each participant will likely do this a small number of times, typically less than ten. The magic sauce is in selecting the pairings. At first the ranking engine looks for pairs that it knows nothing about, but over time it begins to select pairings that help sort between similarly ranked objects. There are also pairs generated to determine if the user is being consistent in their evaluations - this helps detect abuse and attempts to manipulate the ranking.

The algorithms for this approach are beyond the scope of this book, but interested readers can learn more by checking the references section. This mechanism is complex and requires expertise in statistics to build, so if a reputation model requires this functionality, leveraging an existing platform is recommended.

Generating Participation Points

Participation Points are typically a kind of karma where the user accumulates varying amounts of publicly displayable points for taking various actions with the application. Many people see these points as a strong incentive to drive participation and the creation of content. But, remember in Chapter 4 Chap_4-First_Mover_Effects where we indicated that points are used as the only motivation for user actions, can lead to pushing out desirable contributions in favor of quick-and-easy, lower quality content. Also see Chap_8-Leaderboards_Considered_Harmful for a discussion of the challenges associated with competitive displays of participation points.

Participation Points Karma is a good example where the inputs (various, often trivial, user actions) don't match the process of reputation generation (accumulating weighted point-values) or the output (named-levels or raw score).

| Activity | Point Award | Maximum/Time |

|

First Participation |

+10 |

+10 |

|

Login |

+1 |

+1/day |

|

Rate Show |

+1 |

+15/day |

|

Create Avatar |

+5 |

+5 |

|

Add show or character to profile |

+1 |

+25 |

|

Add friend |

+1 |

+20 |

|

Be friended |

+1 |

+50 |

|

Give best answer |

+3 |

+3/question |

|

Have a review voted helpful |

+1 |

+5/review |

|

Upload a character image |

+3 |

+5/show |

|

Upload a show image |

+5 |

+5/show |

|

Add show description |

+3 |

+3/show |

|

Reputation Models |

Points |

|

Inputs |

Raw point value (This is risky if dispirit apps are providing input. Out of range values can do significant social damage to your community.) An action-type index value for a table lookup of points (This is safer. The points table stays with the model, where it is easier to limit damage and track data trends.) |

|

Processes |

(Weighted) Accumulator |

|

Common uses |

Motivation of creating user generated content Ranking in Leaderboards to engage most active users Rewarding specific desirable actions Corporate: Identifying influencers/abusers for extended support/moderation Combined with quality karma in creating |

|

Pros |

Easy to setup and for users to understand Computation is trivial and speedy There are certain classes of users who respond positively and voraciously to this sort of incentive. (See Chap_6-Egocentric_Incentives ) |

|

Cons |

Getting the points-per-action formulation right is an ongoing process as users respond play the minimum effort for maximum point gain game. The correct formulation takes into account the effort required as well as the value of the behavior. (See Chap_6-Egocentric_Incentives ) Points are a discouragement to many of those with altruistic motivations. (See Chap_6-Altruistic_Incentives and Chap_8-Leaderboards_Considered_Harmful ) |

Points systems are increasingly being used as game currencies. Companies such as Zynga make social games that generate participation points that can be spent in-game for special benefits, such as unique items or power-ups to improve the user's experience. This practice has exploded with the introduction of the ability to purchase these same points for hard currency, such as US dollars.

When considering any points-as-currency scheme, keep in mind that this transformation once again shifts the kind of motivations, further away from altruism and now introducing a commercial driver - as now the points reflect, and maybe even exchangeable for, real money.

Even if the points aren't officially purchasable from the application and can only be spent on in-application virtual items, a commercial market may arise for them. A good historical example of this is the sale of game-characters for popular online multiplayer games, such as World of Warcraft. The character levels are representations of participation/experience points and that represents a real investment of time/money. For more than a decade, people have been power-leveling characters and selling them on eBay, even for thousands of dollars.

We recommend against turning reputation points into a currency of any kind unless your application is a game and it is central to your business goals. A further discussion of online economies and how they interact with reputation systems is beyond the scope of this book, but there is an ever increasing about of literature on the topic of RMT: Real Money Trading readily available on the internet.

Generating Compound Community Claims

Compound Community Claims reflect multiple separate, but related, aggregated claims about a single target and include such things as Reviews and rated Message Board posts. But the power of attaching compound inputs of differing types from multiple sources provides a means for allowing users to understand multiple facets of an object's reputation.

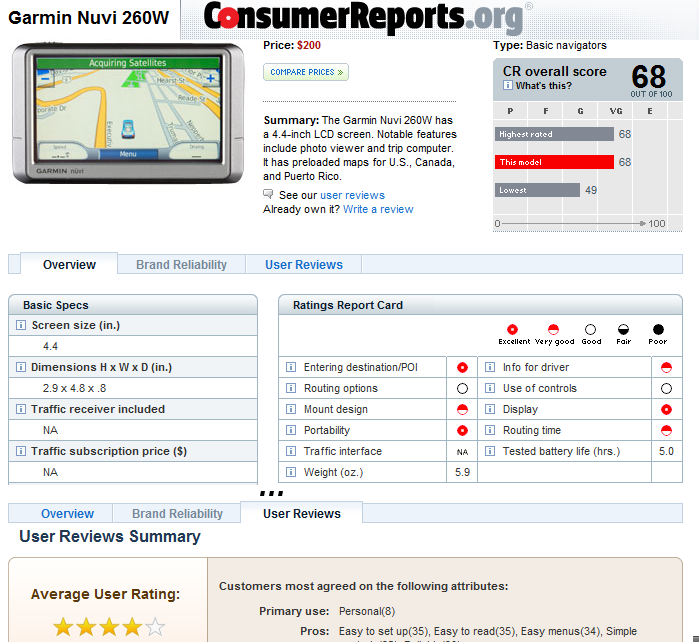

For example, Consumer Reports.org generates two sets of reputation for the objects: the scores generated as a result of the tests and criteria set forth in their labs and the average user ratings and comments provided by their customers via the online site. These can be displayed side-by-side to allow consumers to evaluate a product on numerous standard measures but also on untested and unmeasured dimensions. For example, the user comments on front-loading clothes washers often mention odors that are the result of formerly top-load washer user's not understanding that a front-loader needs hand-drying after every load. This kind of subtle feedback can not be captured in qualitative measures.

Though compound community claims can be built out of diverse inputs from multiple sources, the Ratings and Reviews pattern is well established and deserves special comment here. Asking a user to create a multi-part review is a very heavyweight activity - it takes several minutes for a thoughtful contribution. Users' time is scarce, and research at Yahoo! and elsewhere has shown that user's often abandon the process if extra steps are added, such as login, new user registration, or multiple screens of input. Even if necessary for business reasons, these barriers to entry will significantly increase the abandon rate for your review creation process. People need a good reason to take time out of their day to create a complex review - be sure to understand your model (See Chap_6-Incentives ) and the effects it may have on the tone and quality of your content. For an example of the effects of incentive on compound community claims. See Chap_6-Friendship_Incentive

|

Reputation Models |

Ratings and Reviews, eBay Merchant Feedback, etc. |

|

Inputs |

All types from multiple sources and source types, as long as they all have the same target |

|

Processes |

All appropriate process types apply - every compound community claim is custom built |

|

Common uses |

User created object reviews Editor-based rollups, such as Movie Reviews by Media Critics. Side-by-side combinations of user, process, and editorial claims. |

|

Pros |

Flexible - Any number of claims can be kept together Easy to globally access - all the claims have the same target. If you know the target ID, you can get all reputation with a single call. Some standard formats are well understood by users, as in the case with Ratings and Reviews. |

|

Cons |

If the user is asked to explicitly create too many inputs, incentive can become a serious impediment to getting a critical mass of contributions. Straying too far from familiar formatting, either for input or output can create confusion and user fatigue. There is some tension between format familiarity and choosing the correct input scale. See Chap_7-Good_Inputs |

Generating Inferred Karma

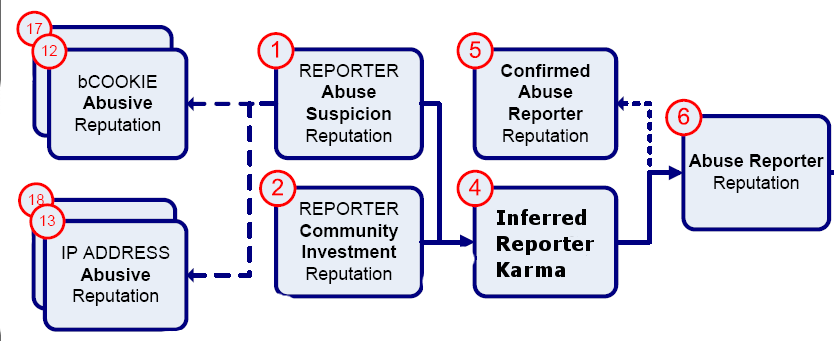

What happens when you'd like to make a value judgment about a user that is new to your application? Is there something other than the general axiom of “No Participation Equals No Trust”? In many cases an inferred reputation score is required - a lower-confidence number that can be used to help make low-risk decisions about the trustworthiness of the user for the application until they can establish an application-specific karma score.

In the case of web applications there are tried and true proxy reputations that may be available even for users that have never crated an object, posted a comment, or even clicked on a single thumb-up. The user's browser possesses session cookies which can hold simple activity counters even for logged-out users, the connection is on an IP address which can have a reputation of its own (if it was recently or repeatedly used by a known abuser), and finally the user may have an active history with a related product what could be considered in a proxy reputation.

Remembering that the best karma is positive karma (See Chap_7-Negative_Public_Karma ), the inferences from these weak reputations can be used to boost an otherwise unknown users reputation from 0 to a reasonable fraction (for example up to 25%) of the maximum value for consideration when weighting their input when they evaluate your objects.

This score is meant only to be used as a temporary part of a <ROBUST KARMA> and, since it is a weak indicator, should provide a diminishing share of the ultimate score as more trustworthy inputs can replace it. One method to accomplish this is to make the inferred share a bonus to the total score (having the total be able to exceed 100%) and then clamping the value to 100% at the end.

|

Reputation Models |

Always custom. Known to be part of: In Chapter_12 we do a case study analysis of Yahoo! Answers and how they use inferred karma to help evaluate contributions by unknown users when those postings are flagged as abusive by other users. WikiAnswers.com also uses inferred karma to limit access to possible damaging actions, such as erasing other user's contributions. |

|

Inputs |

Application external values, examples include: User account longevity I.P. Address abuse score Browser cookie activity counter or help-disabled flag External trusted karma score |

|

Processes |

Custom Mixer |

|

Common uses |

Partial karma substitute - separating the partially known from the complete strangers Help system display - unknown users get extra navigation help Dangerous feature lockout, such as content editing until the user has demonstrated some familiarity with, and lack of hostility to, the application Deciding when to route new contributions to customer care for moderation |

|

Pros |

Allows applications to lower the barrier for some user contributions significantly lower than otherwise possible - for example not requiring registration or login. Corporate karma - no user knows this score and the application can change the calculation method freely as the situation evolves and new proxy reputations become available. Helps bullet-proof your application against accidental damage caused by drive-by users. |

|

Cons |

This karma is, by construction, unreliable. For example, since people can share an IP address over time without knowing it or each other, including it can undervalue an otherwise excellent user by accident. Though one might be tempted to remove IP reputation from the inferred karma , it turns out to be the strongest indicator of a bad user - they don't usually go through the trouble of getting a new IP address whenever they want to attack your site. This karma can be expensive to generate. How often do you want to update the supporting reputations, such as IP or cookie reputation? Every single HTTP round-trip is cost prohibitive, so smart design is required. This karma is weak. It should not be trusted alone for any legally or socially significant actions. |

Practitioner's Tips

Negative Public Karma

Because an underlying karma score is a number, product managers often misunderstand the interaction between numerical values and online identity. It goes something like this:

- In our application context, the users value will be represented by a single karma, which is a numerical value.

- There are good, trustworthy, users and bad, untrustworthy, users and everyone would like to know which is which, so we will display their karma.

- We should have good actions be positive numbers in the karma, and bad actions be negative and we'll add them up to make our karma.

- Good users will display high positive score (and people will interact with them), and bad users will have a low negative score (and people will avoid them).

This thinking –though seemingly intuitive – is impoverished, and is wrong in at least two important ways:

- There can be no negative public karmas - at least for establishing the trustworthiness of active users. A sufficiently bad public score will simply lead to that user abandoning the account, a process we call Karma Bankruptcy. This defeats the primary goal - to publicly identify the bad actors. Assuming a karma starts at zero (0) for a brand new user that an application has no information about, it can never go below zero, since karma bankruptcy (creating a new account) resets it! Just look at eBay Merchant Karma for any seller with more than three red stars - they haven't sold anything in months or years because the merchant either quit or is now doing business under another account name.

- You really don't want to accumulate positive and negative inputs into a single public karma score. Think about it - you encounter a user with 75 karma points and another with 69 karma points - who is more trustworthy? You can't tell, as it may be that the first user used to have hundreds of good points and has been burning them at a mad rate recently and the second user has never received a negative point at all. If you must have public negative reputation, eBay Merchant Feedback shows a much better pattern for handling it: as a separate score.

Even eBay with the most well known example of public negative karma, it doesn't represent how untrustworthy an actual seller is - it only gives buyers reasons to take specific actions to protect themselves. Generally, negative public karma should be avoided. If you really want to know who the bad guys are, keep the score separate and make it a corporate karma - meant only for moderation staff to take appropriate action.

Virtual Mafia Shakedown: Negative Public Karma

The Sims Online was a muliplayer version of the popular Sims games by EA/Maxis where the user controlled an animated character in a virtual world with houses, furniture, games, virtual currency (called Simoneans), rental property, and social activities. Yes, it was playing dollhouse online.

One of the features to support user socialization in the game was ability to declare that a user was a trusted friend. There was a graphical display that showed the faces of the users who said you were trustworthy outlined in green and attached in a hub-and-spoke pattern to your face in the center. People checked each other's hubs to help them decide if they would take certain in-game actions, such as becoming roomates in a house - an action that is too costly for new users alone.

That was fine as far as it goes, but unlike other social networks, The Sims Online allowed people to declare that you were untrustworthy as well. This attached their face with a bright red circle to your otherwise lovely all green friends hub.

It didn't take long for a group, calling themselves the Sim's Mafia to figure out how to use this mechanic to shake down new users when they arrived in the game. The dialog would go something like this: “Hi! I see from your hub that you are new to the area. Give me all of your Simoleans or my friends and I will make it impossible to rent a house…” “What are you talking about?” “I'm a member of the Sim's Mafia, and we will all mark you as untrustworthy, turning your hub solid red (with no more room for green) and no one will play with you. You have five minutes to comply. If you think I'm kidding, look at your hub - three of us have already marked you red. Don't worry, we'll turn it green when you pay…”.

If you think this is a fun game, think again - a typical response to this shakedown was for the user to decide that the game wasn't worth paying $10.00/month for. Playing dollhouse didn't usually involve gangsters.

Avoid public negative reputation. Really.

Draw your diagram!

With goals, objects, inputs, and reputation patterns in hand, at this point it should be possible to draw a draft reputation model diagram and sketch out the flows in enough detail to generate the following questions: What data will I need to correctly formulate these reputation scores? How will I collect the claims and transform them to inputs? Which of those inputs will need to be reversible and which are disposable?

If you are using this book as a guide, try sketching a model out now, even before you consider creating screen mock-ups. One approach we've often found helpful is to start on the right-hand side of the diagram, with the reputations you want to generate and work your way back to the inputs. Don't worry about the calculations at first, just draw a process box with the name of the reputation inside and a short note as to the general nature of the formulation, such as Aggregated Acting Average or Community Player Rank.

Once the boxes are down, connect them up with arrows, where appropriate. Then consider what inputs go into which boxes and don't forget that the arrows can split and merge, as needed.

Only after you have a good rough diagram, then start to dive into the details with you development team - there are many mathematical and performance related details that will effect your reputation model design. We've found that reputation systems diagrams are excellent as requirements documentation and make the technical specification easier to generate while making the overall design accessible to non-engineers.

Of course, there is no application unless these reputation are displayed and/or utilized by the application, and these are the topics of the next two chapters.