Planning Your System's Design

Asking the Right Questions

When planning your reputation system-as with most endeavors in life-you'll get much better answers out of the process if you spend a little time upfront considering the right questions. This is the point where we'll pause to do just that. We'll explore some very simple questions-Why are we doing this? What do we hope to get out of it? How will we know we've succeeded?

The answers to these questions will undoubtedly be not quite so simple. Community sites on the Web vary wildly in their makeup: different cultures, customs, business models and rules for behavior. Designing a successful reputation system means designing a system that's successful for your particular set of circumstances. Which means that you'll need to have a fairly well-tuned understanding of your community and the social outcomes that you hope to affect.

We'll get you started. Some careful planning and consideration now will save you a world of heartache later.

The questions we'll help you answer in this chapter are:

- What are your goals for your application?

- Is generating revenue based on your content a primary focus of your business?

- Will user activity be a critical measure of success?

- What about loyalty (keeping the same users coming back month after month)?

- What is your Content Control Pattern?

- Who is going to create, review, and moderate your site's content and/or community?

- What services do staff and professional feed content or external services provide?

- What roles do the users play?

Based on the answer to these questions, you will find out how comprehensive a reputation system you need. In some cases this will be none at all! Each content service pattern includes recommendations and examples of incentive models to consider for your system.

- Given these goals and content models, what types of incentives are likely to work well for you?

- Should you rely on altruistic, commercial, or egocentric incentives or some combination of them?

- Will karma play a role in your system? Should it?

Understanding how the various incentive models have been demonstrated to work in similar environments will narrow down the choices you make as you proceed to Chapter_7 .

What are your goals?

Marney Beard was a long-time design and project manager at Sun Microsystems, and she had a wonderful guideline for participating in any team endeavor. Marney would say “It's alright to start selfish. As long as you don't end there.” (This was actually advice that Marney first gave her kids, but it turns out to be equally applicable in the compromise-laden world of product development.)

So, following Marney's excellent advice, we encourage you to-for a moment-take a very selfish and self-centered view of your plans for a rich reputation system for your website. Yes, ultimately, your system will be a balance between your goals, your community's desires, and the tolerances and motivations of everyone that comes to the site. But-for now-let's just talk about you.

Both content and people reputations can be used to strengthen one or more aspects of your business. There is no shame in admitting this! As long as we're starting selfish, let's get downright crass. How can imbuing your site with an historical sense of people and content reputation help your bottom line?

User Engagement

Perhaps you'd like to deepen user engagement-either the amount of time that users spend in your community, or the number and breadth of activities that they partake in. For a host of reasons, more-engaged users are more-valuable users, both to your community and to you from a business sense.

Offering incentives to users may persuade them to try more of your offering than their own natural curiosity alone would. Offline marketers have long been aware of this fact-promotions such as sweepstakes, contests and giveaways are all designed to influence customer behavior and deepen engagement.

User engagement can be defined in many different ways. Eric T. Peterson offers up a pretty good list of basic metrics for engagement. He posits that those users are most engaged who:

- view critical content on your site

- have returned to your site recently (multiple visits)

- return directly to your website some of the time (not via a link)

- have long sessions, with some regularity, on your site

- have subscribed to at least one of your site's available data feeds

List adapted from http://blog.webanalyticsdemystified.com/weblog/2006/12/how-do-you-calculate-engagement-part-i.html This list is good, though it is definitely skewed toward an advertiser's or a content-publishers view of engagement on the Web. It's also loaded with subjective measures. (For example, what constitutes a “long” session? Which content is “critical?”) But that's fine! We want subjective-at this point, we can tailor our reputation approach to exactly what we hope to get out of it!

So what would a good set of metrics be to determine community engagement on your site? Again, the best answer to that question for you will be intimately tied to the goals that you're trying to achieve.

Tara Hunt, as part of a longer discussion on Metrics for Healthy Communities offers the following suggestions: * the rate of attrition in your community, especially with new members

- the average length of time it takes for a newbie to become a regular contributor

- multiple community crossover-if your members are part of many communities, how do they interact with your site? Flickr photos? Twittering? Etc.?

- the number giving as well as the receiving actions-eg. readers receive, posters are giving (advice, knowledge, etc.).

- community participation in gardening, policing and keeping the community a nicer place (eg. people who report content as spam, people who edit the wiki for better layout, etc.)

List adapted from http://www.horsepigcow.com/2007/10/03/metrics-for-healthy-communities/

This is a good list, but still highly subjective. Once you decide how you'd like your users to engage with your site and community, then you'll need to determine how to measure that engagement.

Speaking of Metrics…

Later, in Chapter_10 , we'll ask you to evaluate your site's performance against the goals that you define in this chapter. Obviously, this exercise will be greatly aided if you have actual data to compare from before you roll out your reputation system to afterward.

It's a good idea to anticipate the metrics that will help you in performance evaluation, and make sure now that your site or application is properly instrumented to provide that data. And, of course, to ensure that data is being logged appropriately and saved for the time when you'll need it for decision-making, tweaking and tuning of your system.

After all, there's nothing quite like doing a 'before and after' comparison, only to realize that you weren't keeping proper data before…

Establishing Loyalty

Perhaps you're interested in building brand loyalty with your visitors, to establish a relationship with them that extends beyond the boundaries of one visit or session. Yahoo! Fantasy Sports employs a fun reputation system, enhanced with nicely-illustrated trophies for achieving milestones (such as a winning season in a league) for various sports.

This simple feature serves many purposes: the trophies are fun and engaging; they may serve as incentive for community members to excel within a sport; they help extend a user's identity and give them a way to express their own unique set of interests and biases to the community; but they are also an effective way of establishing a continuing bond with Fantasy Sports players-one that persists from from season to season and sport to sport.

Any time a Yahoo! Fantasy Sports user is considering a switch to a competing service (Fantasy Sports is big business! there are any number of very capable competitors in the space), the presence of these trophies provides tangible evidence of the switching cost for doing so: a reputation reset.

Coaxing Out Shy Advertisers

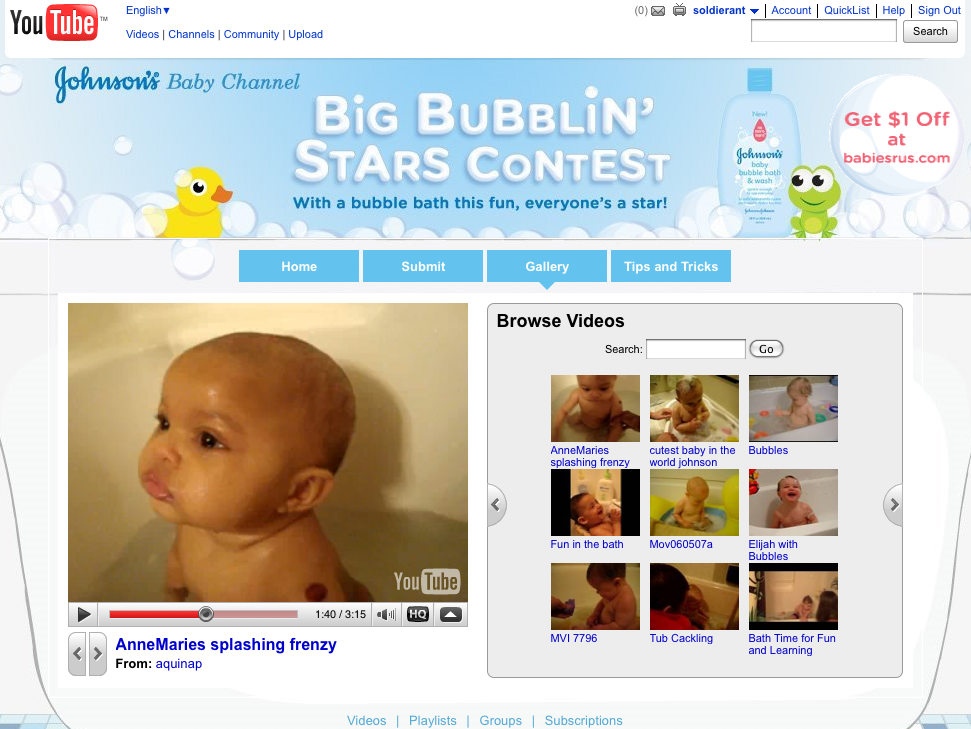

Maybe you are concerned about your site's ability to attract advertisers. User-generated content is a hot Internet trend that's almost become synonymous with Web 2.0, but it has also been slow to attract advertisers. Particularly those big, traditional (but deep-pocketed!) companies who worry about the effect of displaying their own brand in close proximity to the Wild-West frontier ethos that's sometimes evident on sites like YouTube or Flickr.

Once again, reputation systems offer a way out of this conundrum. By tracking the high-quality contributors and contributions on your site, you can guarantee to advertisers that their brand will only be associated with content that meets or exceeds certain standards of quality.

In fact, you can even craft your system to reward particular aspects of contribution. Perhaps, for instance, you'd like to keep a 'Clean Contributor' reputation that takes into account a user's typical profanity level, and also weighs abuse reports against him or her into the mix. Without some form of quality-and-legality-based filtering, there's simply no way that a prominent and respected advertiser like Johnson's would associate their brand with YouTube's (typically anything-goes) user-contributed videos.

Of course, another way to allay advertisers' fears is by generally improving the quality (both real and perceived) of content generated by the members of your community…

Improving Content Quality

Reputation systems really shine at helping you make value judgements about the relative quality of content that users submit to your site. Chapter 9 will focus on the myriad techniques for filtering out bad content and encouraging good quality contributions. For now, it's only necessary to think of “content” in broad strokes: first let's identify what the patterns for content generation and management on our site are. This will help us make some smarter decisions about our reputation system.

Content Control Patterns

Whether you need reputation at all, and the particular models that will serve you best, are largely a function of how content is generated and managed on your site. Consider the workflow and life-cycle of content that you have planned for your community, and the various actors that will influence that workflow.

First, who will be touching your communities content-will users be doing the bulk of content creation and management? Or staff? (We'll generically refer to these people as 'staff', but they could be people under your employ, or trusted third-party content providers, or even 'deputized' members of the community, depending on the level of trust & validation that you put into them.)

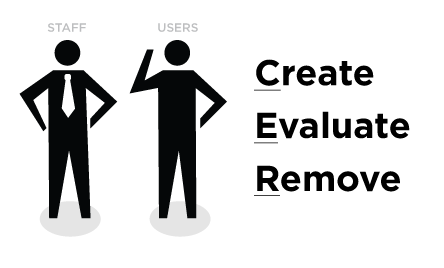

In most communities, you'll find that content control is a function of some combination of users and staff. Therefore, it's worth our while to dissect the types of activities that each might be doing. Consider all the potential activities around the content lifecycle at a very granular level:

- Who will draft the content?

- Will anyone edit it, or otherwise determine its readiness for publishing?

- Who is responsible for actually publishing it to your site?

- Can anyone edit content that's live?

- Can live content be evaluated in some way? Who will do that?

- What effect does evaluation have on content?

- Promote or demote its prominence?

- Remove it altogether from the site?

While you'll ultimately have to answer all of these questions, at this stage these fine-grained questions can be abstracted somewhat. Right now, there are really three questions you need to pay attention to:

- Who will create the content on your site? Users or staff?

- Who will evaluate the content?

- Who has responsibility for removing content that is inappropriate?

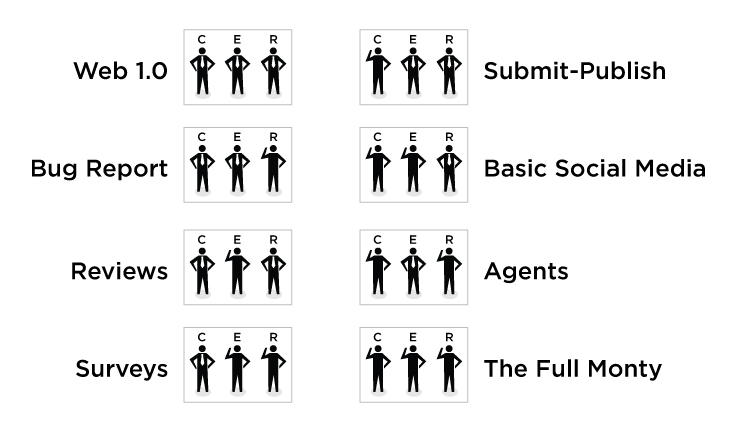

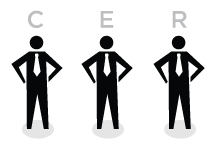

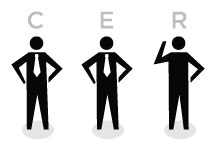

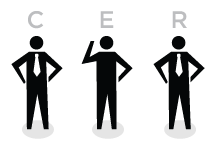

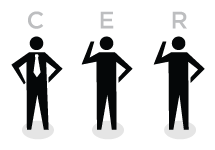

There are eight different content control patterns for each unique combination of answering the questions above. Each pattern has unique characteristics when considering what reputation systems you may, or may not, wish to consider for your application. For convenience, we've given each pattern a name as seen in Figure_6-4 : Web 1.0, Submit-Publish, Bug Report, Reviews, Surveys, Agents, Basic Social Media, The Full Monty, but these names are just place holders for discussion, they are not a suggestion to recategorize your product marketing. We will now cover each of these content control patterns in detail so you will understand the implications and ramifications of each.

<note>If you have multiple content control patterns, consider them all and focus on any shared reputation opportunities. For example, you may have a community site with a hierarchy of categories that are created, evaluated and removed by staff, but perhaps the content within that hierarchy is created by users. In that case, two patterns apply: the staff-tended category tree is an example of the Web 1.0 content control pattern and as such it can effectively be ignored when selecting your reputation models. Focus instead on the options suggested by the Submit-Publish pattern formed by the users populating the tree.

Web 1.0: Staff Create, Evaluate, and Remove

When your staff is in complete control of all of the content on your site-even if it is supplied by third party services or data feeds-then you are using a Web 1.0 content control pattern. There's really not much a reputation system can do for you in this case-no user participation equals no reputation needs. Sure you could grant users reputation points for visiting pages on your site or clicking on things, but to what end? Without some sort of visible result coming out of their participation, they will soon give up and go away.

It is probably also not worth the expense to build a content reputation system for use solely by staff, unless you have hundreds of staff evaluating tens of thousands of items or more. If you are in that situation, re-evaluate your answers when considering these content control patterns, this time imagine that your large staff are the users of your application.

Bug Report: Staff Create and Evaluate, Users Remove

In this pattern, the users are encouraged to petition for removal or major revision of items in a staff-created and -reviewed database. The users don't add any content that other users can interact with, but provide feedback that is intended to eventually change the corporate content. Examples include bug tracking and customer feedback platforms and sites, such as Bugzilla and getsatisfaction.com. Each allows users to tell the provider about an idea or problem that they had, but doesn't have any immediate effect on the product or other users.

A simpler form of this pattern is when users simply click on button to report the content as inappropriate, in bad taste, old, or a duplicate. The software decides when to hide the content item in question. AdSense, for example, allows customers who run sites to mark specific advertisements as inappropriate matches for their site-teaching Google about the user's preferences.

Typically this pattern doesn't require a reputation system-user participation is a rare event and may not even require a validated login. In cases where a large number of interactions per user are appropriate, a corporate reputation reflecting how effective the user is at performing a task can be helpful in quickly prioritizing submissions from the best contributors.

This pattern is similar to the Chap_6-Submit-Publish-CCP , though the moderation process is typically less socially-oriented than a review (since the feedback is intended for the feedback-provider only.) Often these systems contain strong negative feedback which is crucial to understanding your business, but not something appropriate for the general public to be able to review.

Reviews: Staff Create and Remove, Users Evaluate

The first generation of online reputation systems, this popular pattern empowered users to leave ratings and reviews of otherwise static web content which was then used to produce rank-ordered lists of like items. Early, and still prominent, sites that use this pattern are Amazon.com, dozens of movie, local, and product aggregators, and even blog comments can be considered to be user evaluation of otherwise tightly controlled content (the posts) on sites like BoingBoing or The Huffington Post.

The simplest form of this pattern is implicit ratings only, such as Yahoo! News, which tracks the most emailed stories for the day and the week. The user simply clicked on a button that said “Email this story” and it produced a reputation rank for the story.

Historically for reviews the users were usually motivated by altruism (see Chap_6-Incentives ), and until strong personal communications tools arrived, such as social networking, newsfeeds and multi-device messaging (connecting SMS, email, the web, etc.) didn't produce as many ratings and reviews as many sites were looking for. Often there was more site content than user reviews, meaning that many content items (an obscure restaurant or specialized book for instance) had no reviews to display.

There have been attempts to use commercial (direct payment) incentives to encourage more and better reviews: Epinions had several forms of user payment for reviews. Almost all of them were eventually shut down, leaving only a revenue sharing model for reviews that are tracked to actual purchases. It seems that in every other case, getting paid was a strong incentive to game the system (generate false helpful votes, etc.), which actually lowered the quality of information on the site! Paying for participation almost never equals quality contributions.

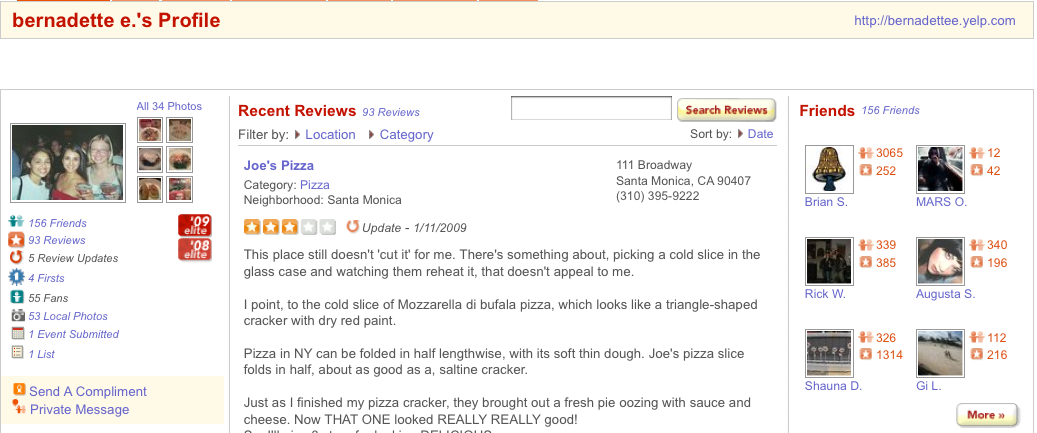

More recently, sites such as Yelp! have created egocentric incentives for encouraging users to create reviews: others users can rate their contributions across dimensions like 'useful', 'funny', and 'cool' and tracking more than 20 public metrics of popularity for their users. This has the effect of encouraging more participation by certain mastery-oriented users, but may be overly specializing the audience for the site by selecting for people with certain tastes.

What makes the reviews pattern special is that it is by and for other users. This is why the “Was this Review Helpful?” reputation pattern has emerged as a popular participation method in recent years-hardly anyone wants to take several minutes to write a review but it only takes a second to click a thumb-shaped button. Now a review itself can have a quality score and its author can have the related karma-in effect, the review becomes its own context and is subject to a different content control pattern: Chap_6-Basic-Social-Media-CCP .

Surveys: Staff Create, Users Evaluate and Remove

The Surveys content control pattern is not that common in public web applications: the users evaluate and eliminate content as fast as staff can feed it to them. This pattern's scarcity is usually because of the expense of supplying content of sufficient minimum quality. Consider this a user-empowered version of the Reviews, where content is flowing so swiftly that only the fittest survive the user's wrath. Probably the most obvious example of this pattern is the television program American Idol and other elimination competitions that depend on user voting to decide what is removed and what remains until the best of the best is selected and the process begins anew. In this example, the professional judges are the staff that select the initial acts (content) that the users will see perform (content) from week to week and the home audience, who votes via telephone act as the evaluators and removers.

The keys to utilizing this pattern successfully are:

- Keep the primary content flowing at a controlled rate appropriate for the level of consumption by the users, and keep the minimum quality consistent or improving over time.

- Make sure that the users have the tools needed to make good evaluations and fully understand what happens to removed content.

- Consider carefully what level of abuse mitigation reputation systems you may need to counteract for any cheating. If your application will result in some content increasing or decreasing significantly in commercial or egocentric value, there will be incentives for people to abuse your system.

This web robot helped get Chicken George to be a housemate on Big Brother: All Stars

Click here to open up an autoscript that will continue to vote for chicken George every few seconds. Get it set up on every computer that you can, it will vote without you having to do anything.

Submit-Publish: Users Create, Staff Evaluate and Remove

When users create content that will be reviewed for publication and/or promotion by the site that is the Submit-Publish content control pattern. There are two common evaluation patterns for the staff review of content: proactive and reactive. Proactive submission review is when the content is not immediately published to the site and is instead placed into a review queue for staff to approve or reject. Reactive submission review trusts the users' content until someone complains. In this pattern, the proactive review process is indicated by the fact that staff does the evaluation and removal of content. Reactive review is the typical case when users are in the evaluator and/or remover roles.

Some web sites that implement this pattern are television content sites, such as for the TV program Survivor. That site asks you to send your video to them directly and they won't republish it unless you are chosen for the show. Citizen news sites such as Yahoo! You Witness News accept photos and videos and screen them as quickly as possible before publishing them to their site. Likewise, food magazine sites may accept recipe submissions that they check for safety and copyright issues before republishing.

Since the feedback loop for this pattern is typically days, or at best hours, and the number of submissions per user is miniscule the main incentives that tend to drive people fall under the altrusism category: “I'm doing this because I think it needs to be done, and someone has to do it.” Attribution should be optional-but-encouraged and karma is not worth calculating since the traffic levels are so low.

An alternative incentive that has proven effective to get short-term increases in participation for this pattern are commercial: offer a cash prize drawing for the best, funniest, or wackiest submissions. In fact, this pattern is used by many contest sites, such as YouTube's “Symphony Orchestra” contest. (http://www.youtube.com/symphony) YouTube had judges sift through user-submitted videos to find exceptional performers to fly to New York City for a live performance a symphony concert of a new piece written for the occasion by the renowned Chinese composer Tan Dun, which was then, republished on YouTube. “How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Upload! Upload! Upload!” - Michael Tilson Thomas, Director of Music.

Agents: Users Create and Remove, Staff Evaluate

The Agents pattern rarely appears as a stand-alone form of content control, but often appears as a sub-pattern in a more complex system. The staff act as a prioritizing filter over the incoming user generated content which is passed on to other users for simple consumption or rejection. A simple example is early web indexes, such as the 100% staff-edited Yahoo! Directory, which was the Web's most popular index until web-search demonstrated that it could better handle the Web's exponential growth and the types of detailed queries required to find the fine-grained content available.

Agents are often used in hierarchical arrangements to provide scale - each layer of hierarchy decreases the work on each individual evaluator by multiple times - this can make it possible for a few dozen people to evaluate a very large amount of user generated content. We mentioned that the contest portion of American Idol was a Surveys content control pattern - but the initial selection of talent for this goes through a series of agents, each prioritizing and passing them on to a judge, and so on until some of the near-finalists (selected by yet another agent) appear on camera before the celebrity judges - who choose those who will be the content during the season. But the celebrity judges do not choose who appears in the qualification episodes - the producer does.

This pattern generally doesn't have many reputation system requirements, depending on how much power you invest in the users in removing content. In the case of the Yahoo! Directory, the company may chose to pay attention to the links that remain unclicked in order to optimize its content. If, on the other hand, your users have a large amount of authority over the removal of content, consider the abuse mitigation issues raised in the Chap_6-Surveys-CCP pattern.

Basic Social Media: Users Create and Evaluate, Staff Remove

Having the users create and evaluate a significant portion of the application's content is what people are calling basic social media these days. Most sites chose to keep staff control over the removing content because of two primary types of reasons:

- Legal Exposure: Compliance with local and international laws surrounding content and who may consume it cause most providers to draw the line on user control here. In Germany, for instance, images of certain Nazi imagery is banned from websites, even if the content comes from an American user, so German sites filter for it. No amount of user voting will overturn that decision. US laws that effect what content may be displayed and to whom include COPPA and COPA (how children interact with identity and advertising) as well as the DCMA - Digital Copyright Millennium Act - which requires sites with user generated content to remove items that are alleged to violate copyright upon the request of the content's copyright-holder.

- Minimum Editorial Quality/Revenue Exposure: When user generated content is popular, but causes the company grave business distress, it is often removed by staff. A good example of when user generated content and business goals conflict surfaces in sites that are monitized by third party advertisements: Ford motor company isn't happy when its advertisements appear on a discussion group next to a thread that says “The Ford Taurus Sucks! Buy a Scion instead.” Even if there is no way to monitor for sentiment, often a minimum quality of contribution is required for the greater health of the community and business. Compare the comments on just about any YouTube video to those on popular Flickr photos. Having staff set the removal bar a bit higher can be helpful.

New sites often try to start out with and empty shell expecting users to create and evaluate en masse, but fail to ever achieve a critical mass of content creators because they didn't account for the small fraction of creators as we discussed in Chap_1-creators_synthesizers_consumers . Assuming you overcome the not-enough-creators bootstrapping problem, though advertising, reputation, partnerships, and/or a lot of hard work, the virtual circle feedback loop can start working for you. See Chap_1-virtuous_circle The web is filled with examples of significant growth with this content control pattern: Digg, YouTube, Slashdot, JPG Magazine, etc.

The challenge comes when you become as successful as you dreamed and two things happen: people begin to value their status as a contributor to your social media ecosystem and you simply can't keep up with the resulting abuse that is being generated on your staff as they attempt to keep up with your popularity. You'll need to plan to implement reputation systems for success - to help users find the best stuff their peers are creating and to allow them to point your moderation staff at the bad stuff that needs attention. Consider content reputation and karma in your application design from the beginning, as it is often disruptive to introduce systems of users judging each other's content after community norms are well established.

The Full Monty: Users Create, Evaluate, and Remove

What? You want to give users complete control over the content? Are you sure? Be sure to read Chap_6-Basic-Social-Media-CCP for reasons that most providers don't hand over most removal control to the community.

We call this content control pattern The Full Monty after the musical about desperate blue-collar guys who've lost their jobs and have nothing to lose, so they let it all hang out at a benefit performance dancing naked with only a hat for covering. It's kinda like that - all risk, but very empowering and a lot of fun.

There are a few obvious examples and contexts where this is appropriate: Wikis were specifically designed for this case - if you have reason to trust everyone with the keys to the kingdom, get the tools out of the way. This pattern has turned out to be great inside of companies and non-profit organizations, and even ad-hoc workgroups. In these cases, some other social control mechanism, such as an employment contract, or being shamed or banished from the group, combined with the power for anyone to restore any damage (intentional or otherwise) done by another is sufficient for these contexts to function well.

But what about public contexts where there is no social contract to limit behavior? Wikipedia, for example is not really this pattern - there is a large cadre of robots and professional editors who are watching every change and enforcing policy in real time - it is much more like Chap_6-Basic-Social-Media-CCP .

When there is no external social contract governing users actions, you need to substitute reputation systems to develop a sense of value for the objects and the users involved in this wide-open ecosystem. Consider Yahoo! Answers, covered in detail in Chapter_11 . They decided to allow the users themselves to remove content visibly from the site because the staff backlog for reviewing abusive content averaged twelve hours response time. This meant that the vast majority of the potential damage by the abuse was already done by the time it was removed. By building a corporate karma system for users that reliably reported abusive content and trusting those users, the average amount of time bad content was up on the site dropped to 30 seconds! Sure, customer care staff was still involved with the hard-core problem cases of swastikas, child abuse, and porn spammers but the vast majority of abusive content is now completely policed by the users.

Note that catching the bad content is not the same is identifying the good. In a universe where the users are in complete control, the best you can hope to do is to encourage the kind of contributions you want through modeling behavior, constantly tweaking your reputation systems, improving your incentive models, and providing clear lines of communications between your company and the customers.

Incentives for user participation, quality, and moderation

Predictably Irrational

In Chapter 4 of his book Predictably Irrational, Duke University Professor of Behavioural Economics Dan Ariely describes a view of two separate incentive exchanges for doing work and the norms that set the rules for them: he calls them social norms and market norms.

Social norms govern doing work for other people because they asked you to-often because doing the favor makes you feel good. Ariely says these exchanges are “wrapped up in our social nature and our need for community. They are usually warm and fuzzy.” Market norms, on the other hand, are cold and mediated by wages, prices and cash: “There's nothing warm and fuzzy about it,” writes Ariely. It is the land of “you get what you pay for.”

Social and market norms don't mix well. Ariely gives several examples of confusion when these incentive models mix: first he describes a hypothetical scene after a family home-cooked holiday dinner where he offers to pay his mother $400.00 and the outrage that would cause (including that the social damage would be take a very long time to repair). The second less purely hypothetical and more common example is about dating and sex. A guy takes a girl out on a series of expensive dates. Should he expect increased social interaction-maybe at least a passionate kiss? “On the fourth date he casually mentions how much this romance is costing him. Now he's crossed the line Violation! … He should have known you can't mix social and market norms-especially in this case-without implying that the lady is a tramp.”

Predictably Irrational then goes on to detail experiments that verify that there are significant differences between social and market exchanges, at least when it comes to very small units of work, much like the kinds of user created content tasks that the designers of web sites are looking to incentivize. The tasks were trivial: use a mouse to drag a circle into a square on a computer screen as many times as possible in five minutes. Three groups were tested - one was not offered any compensation, one was offered $0.50 the last was offered $5.00 for their time. Though the group paid $5 did more work than the one paid 50 cents,the group that did the most work were those who were not offered any money at all! When the money was substituted with a gift of the same value (Snickers Bar and a box of Godiva Chocolate), the work distinction went away - it seems that gifts behave in the domain of social norms and everyone worked as hard as those that were uncompensated. But! When the price sticker is left on the chocolates so that the subjects can see the monetary value of the reward, the market norms again applied and the striking difference in work results returns - volunteers again worked harder than those who received priced chocolates.

Incentives and Reputation

When considering how a reputation system might help with your content control pattern, be careful to consider the appropriate incentives for your users and the tasks you are asking them to do on your behalf. But also remember that you have particular goals for your application - sometimes this may lead selecting a different reputation model - try to accommodate both sets of needs.

Ariely talked about two categories of norms - social and market, but for reputation systems we talk about three main groups of online incentive behaviors: altruistic (for the good of others), commercial (to generate revenue), and egocentric (for self gratification). Interestingly these map somewhat against social norms (altruism & egocentric) and market norms (commercial & egocentric). Notice that egocentric is listed under both norms, something usually to be avoided. This is because market-like reputation systems (points and virtual currencies) are being used to create successful work incentives for these users. In effect, egocentric crosses the two exchanges by creating a entirely new virtual world where these norms can co-exist in ways that we would find socially repugnant in the real world - in these worlds bragging is good!

Altruistic (Sharing) Incentives

The altruistic incentives represent the giving nature of the user - they have something to share - a story, a comment, a photo, an evaluation, etc. and they feel compelled to share it on your site. Their incentives are internal - even if they include a feeling of obligation to another user, a friend, or even loyalty (or hatred) for your brand.

The altruistic or sharing patterns are: Tit-for-Tat/Pay-it-Forward (because someone else did it for me first), Friendship (because I care about those who will consume this), Know-it-all/Crusader/Opinionated (because I know something everyone else needs to know). This list is incomplete - if you know of others, please contribute them to the website for this book: [LINK]BuildingReputation.com.

When considering reputation models that create altruism incentives, remember that this is the realm of social norms - it is all about sharing, not about accumulating commercial value or karma points. Avoid aggrandizing the creator of altruistically-created content-they don't want their contributions to be counted, recognized, ranked, evaluated, compensated, or rewarded in any significant way. Comparing their work to anyone else's will actually discourage them from participating.

Tit-for-tat/Pay It Forward

Tit-for-tat is when a user decides to contribute based on a feeling of obligation to pay back a favor because they received benefit from either the site or from the other users of the site. In early social sites with content control patterns like Reviews, where users only evaluate staff provided content, there were no site-provided incentives to participate and users most often indicated that they contributed because a review on the site helped them.

Pay It Forward (from the book written by Catherine Ryan Hyde and the resultant motion picture in 2000) describes the following: improve the state of the world by doing a unconditional and unrequested deed of kindness to another - with the hope that the recipient would do the same thing for one or more other people creating a never ending and always expanding world of altruism. We mention it here so that you might consider it as a model for corporate reputation systems that track altruistic contributions as an indicator of community health.

In fall of 2004, when the Yahoo! 360° social network first introduced the vitality stream (now known as the personal news feed and improperly attributed as being invented by Facebook who copied it years later) it included events that were generated whenever your friends wrote a review of a restaurant or hotel for Yahoo! Local. From the day the service was opened to the public, Yahoo! Local saw a 45% sustained lift in the number of reviews written daily!

The knowledge that friends would be notified when you wrote a review - in effect notifying them both of where you went and what you thought - became a much stronger altruistic motivator than Tit-for-tat. In the sited example above, a Yahoo! 360° user was greater than fifty (50!) times more likely to write a review than a typical Yahoo! Local user. There's really no reputation system involved here, you simply make sure that friends can see the things that each other contribute to the site - either through news feed events or when a user searches for an item, or whenever they happen to encounter something a friend did before.

Know-it-all/Crusader/Opinionated

Lastly, there are people who have an internal motivation based on passion. Some of the passion is temporary, such has having a terrible customer experience and wishing to share their frustration with the anonymous masses and perhaps exact some minor revenge on the business in question. Some of the passion is the result of deeply held beliefs, such as religion or politics. Some is topical expertise and others are just killing time. In any case, people seem to have a lot to say that is of very mixed commercial value. Look at the comments on a YouTube video, but not for very long, your eyes might bleed.

This group of altruistic motivations is a mixed bag - there are great contributions in here, but there's also a lot of junk as we mentioned in Chap_1-lots_of_crap . If you have reason to believe that a large portion of your most influential community members will be motivated by controversial ideas, carefully consider the costs of your evaluation and removal choices for your content control pattern. A large out-of-control community can be worse than having no community at all.

Go to any movie review site and look at the reviews for Fahrenheit 9/11 and The Passion of the Christ and look how people respond to each other's reviews. If the reviews have “Was this review helpful?” voting, look at the reviews with the highest total votes and how polarized they are. Clearly the word helpful in this context now means agreement with the author.

Commercial Incentives

Commercial incentives fall squarely in Ariely's market norms - people are doing this for the money, though the money may come in the form of direct payment from the user to the content creator. Advertisers have a nearly scientific understanding of the significant commercial value of something they call branding. Likewise, influential bloggers know they are posting to build their brand, often to become perceived as subject matter experts which may lead to improved standing - speaking engagements, consulting contracts, improved permanent positions at universities or prominent corporations, or even a book deal. A few may actually be directly paid to produce their online content, but more are capturing indirect commercial value.

Reputation models in content control patterns with commercial incentives requires a much stronger sense of user identity and will need strong and distinctive profile thats provide links to their valuable contributions and content. An expert in, say the area of textile design will want, as part of their personal brand, a way to share a set of links to content that they think is particularly noteworthy to their fans.

But, don't confuse the need to support a strong profile/brand for the contributor with the need for a strong or prominent karma system. When a new brand is being introduced to a market, be it a new kind of dish soap or a new topical blogger, a karma system that favors established participants can be a disincentive. The community decides how to treat newcomers - with open arms or with suspicion. An example of the latter is eBay - where every new seller must “pay their dues” and bend over backward to get their first dozen or so positive evaluations before the market at large will embrace them as a trustworthy vendor. The goals of your application should help you decide if you need karma in your commercial incentive model. One possible rule of thumb: If users are going to be passing money directly to other people they don't know, consider adding karma to help establish trust.

Direct Revenue

By direct revenue we mean: whenever someone forks over hard-earned cash for the consumption of the content contributor's work and it ends up, sometimes via an intermediary or two, in the contributor's hands. This could be the result of a subscription, short term contract, a goods or services transaction, on-content advertising like Google's AdSense, or even a PayPal-based tip jar.

When it comes to real money, people get serious about issues of trust, and reputation systems play a critical role in helping establish trust. Without a doubt, the most well known and studied - reputation system for online direct revenue business is eBay's buyer and seller feedback (karma) system. Without a way for strangers to gage the trustworthiness of the other party, there could be no online auction market at all.

When considering reputation systems for applications with direct revenue incentives, step back and make sure that you might not be better off with an either altruistic or egocentric model - despite what you may have been taught in school, money is not always the best motivator and is a pretty big barrier to entry for consumers. The ill-fated Google Answers failed because it had a user-to-user direct revenue incentive model where competing sites, such as WikiAnswers provided similar results for free financed, ironically, by using AdSense to monetize answer pages which are indexed by, you guessed it, Google!

The Zero Price Effect: Free is disproportionately better than cheap!

In Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely details an series of experiments to show that people have an irrational urge to chose a free item over a unusually low-priced but higher quality item: First he offered people a single choice between buying a 1-cent Hershey's Kiss and a 15-cent Lint truffle and most people bought the higher quality truffle. But, when he dropped the price both items by one penny, making the Kiss free, a dramatic majority of a new group of buyers instead selected the Kiss! He calls this the Zero Price Effect. For designing incentive systems it provokes two thoughts:

- Don't delude yourself that sufficiently low-pricing in a user-to-user direct revenue incentive design will overcome the Zero Price Effect.

- Even if you give away user contributions for free you can still have direct revenue: charge advertisers/sponsors instead of the consumers directly.

Branding - Professional Promotion

The indirect form of commercial incentives can be lumped under the word branding, the process of professional promotion of people, goods, or organizations. The advertiser's half of the direct revenue incentive model lives here as well. The goal is to expose the audience to your message and eventually capture value in the form of a sale, subscriber, or job.

There is typically a large number of steps between branding activities: writing blog posts, running ads, creating widgets to be embedded on other sites, participating in online discussions, attending conferences, etc. and the desired effects. Reputation systems are one way to have users close the loop with direct feedback as well as help measure the success of these activities.

Take the simple act of sharing a URL on a social site, such as Twitter - without a reputation system you have no idea how many people followed your recommendation, nor how many other people shared it as well. The URL-shortening service Awe.sm provides both features - it tracks how many people clicked on your URL and how many different people shared the URL with others.

For contributors that are building their brand, public karma systems are a double-edged sword - when they are at the top of their perspective markets, their karma can be seen as a big indicator of trustworthiness. For new entrants, most karma scores can't differentiate between inexperience (or just coming to the web-game later than peers) and incompetence. This problem can be addressed by making sure to including the ability to include time-limited scores in the mix. For example, B.F. Skinner is a world renowned and respected behaviourist, but that does me no good when I'm looking for a thesis advisor-he's been dead for almost 20 years.

Egocentric Incentives

Found online most often in computer games, egocentric incentives are tied to deeply wired self-centered motives. The simplest and most important egocentric goal is are the desire to accomplish a task. Get it done and move on.

But some of egocentric incentive systems tap into motivations are described in behavioral psychology with terms such as a classical/operant conditioning (where animals were trained to respond to food-related stimulus) and schedules of reinforcement: fixed, continuous, and variable, interval and ratio- all leading to the conclusion that people can be influenced to repetitively perform simple tasks by providing periodic rewards, even if as simple as a pleasing sound.

Care must be taken with considering the powerful effects of using reputation to drive egocentric incentives. Looking at an individual animal's behavior in a social vacuum, as many of the classical behaviorists did does not accurately represent how we very-social humans reflect our egocentric behaviors to each other. Humans make teams and compete in tournaments. We follow leader boards comparing our selves - even our companies' - performance to others. Even if it doesn't help another soul or generate us any revenue, we often want to feel recognition for our accomplishments. Even if we don't seek accolades from our peers, we want to be able to demonstrate mastery of something - to hear that little feedback from a system that says “You did it! Good Job!”

When creating reputation systems utilizing egocentric incentives, a user profile becomes a critical requirement of your system. The user needs some place to show off their accomplishments - even if only to themselves. Almost by definition, egocentric incentives are one or more forms of karma. Even if you select a simple system of granting trophies for achievements, the users will compare their collections to each other. New norms will appear that look more like market norms than social norms: people will trade favors to both advance their karma, people will attempt to cheat to get an advantage, and those who feel they can't compete will opt-out all together!

Yes, egocentric incentives and karma provide very powerful motivations, but these are almost antithetical to altruistic ones. There have been many systems that have over-designed to reinforce the egocentric gaming contingent and ended up with an almost entirely experts-only customer base: consider just about any online role playing game that survived more than three years. For example, Worlds of Warcraft must continually produce new content for it's highest-level users in order to retain them and their revenue stream, all but abandoning improvements to increase its acquisition of new users - stunting growth. When new users do arrive (usually the result of a marketing promotion), they end up playing alone because all the veterans are too advanced and their focus is solely on the new content. They don't want to bother with going through the leveling process again.

The simplest egocentric incentive is the desire to complete a task, to fulfill a goal as labor or personal enjoyment. Many reputation model designs tap the user's desire to accomplish a complex task can generate knock-on reputations for use by other users or the system as a whole. For example, free music sites use the user's desire to customize their personal radio station to gather ratings that they can then use to better recommend music to other users. Not only can reputation models that fulfill preexisting user needs gather more reputation claims that altruism and commercial incentives can - the data is typically of higher quality since it more closely represents the user's true desires.

Recognition

The outward-facing egocentric incentives are all related to personal or group recognition. The reflection of others admiration, praise or even envy is the desire that drives this group. It's all about the reputation score and that's all there is to it. Often this is shown as one or more public leader boards, but could appear as events in a user's newsfeed, such as the messages sent by Zynga's Mafia Wars telling all your friends that you became a Mob Enforcer before they did, or that you gave them the wonderful gift of free energy that will help them get through the game faster.

Recognition is a very strong motivator for many users, but not all. If, for example, you give points that accumulate for user actions in a context where altruism or commercial motivations produce the best contributions, you will end up with your highest quality contributors leaving the community while those who churn out lesser value content fill your site with clutter.

Always consider implementing a quality based reputation system along side any recognition/ego incentives to provide some balance between quality and quantity. See (XXX) for examples of how Digg, Little Planet, and City of Heroes were hijacked by people gaming user recognition reputation systems to the point of seriously decreasing the quality of the applications key content.

The Quest for Mastery

The personal or private forms of egocentric incentives can be summarized as a quest for mastery. Consider when people play solitaire or crossword or sudoku puzzles alone - they are doing it simple for the stimulation and to see if they can accomplish a specific goal - beat a personal score or time or even just complete the game at all. The same is true for all single-player computer games, which are much more complex. Even multiple player games, online and off, such as Scrabble or World of Warcraft have strong personal achievement components, such as bonus multipliers or character mastery levels.

Of particular note is that online single player computer games - or casual game sites - as they are known in the industry skew disproportionately female and older than most game stereotypes you may have encountered. [CITE STATS HERE] So, if your application expects to use ego incentives and you're expecting more women that men, consider staying away from recognition systems and instead looking at mastery based incentive systems.

Some common mastery systems include achievements (personal feedback that they have accomplished one of a set of multiple goals), Ranks/Levels with Caps (Discrete increasing performance acknowledgements such as Ensign, Corporal, Lieutenant, General, but with a clear achievable maximum), or performance scores like percent accuracy where 100% is the desired perfect score.

Resist the temptation to keep extending the top-tier of your mastery system, as this leads to user fatique and abuse. Let the user win. It's OK. They've already given you a lot of great contributions and will likely move on to other areas of your site that need attention.

Consider Your Community

Introducing a reputation system into your community will almost certainly affect its character and behavior in some way. Some of these effects will be positive (hopefully! I mean, that's why you're reading this book, right?) But there are potentially negative side-effects to be aware of as well. It is almost impossible to predict exactly what community effects will result from implementing a reputation system because-and we bet you can guess what we're going to say here!-it is so bound to the particular context that you are designing for. But here are a number of community factors to consider early in the process.

What are people here to do?

This may seem like a simple question, but it's one that often goes unasked: what, exactly, is the purpose of this community? What are the actions, activities and engagements that they expect when they come to your community? Will these actions be aided by the overt presence of content-or-people-based reputations? Or will the mechanisms used to generate those reputations (event-driven inputs, visible indicators, and the like) actually detract from the primary experience that your users are here to enjoy?

Is this a new community? Or an established one?

Many of the models and techniques that we're covering are equally applicable whether your community is a brand-new, aspiring one or has been around awhile and already enjoys a certain dynamic. However, it may be slightly more difficult to introduce a robust reputation system into an existing and thriving community than it would have been to bake reputation in from the beginning. Why is this?

- In an established community, there are already shared mores and customs. Whether the community rules have been formalized or not, there are indeed expectations for how to participate in the community. As well as an understanding of what types of actions and behaviors are viewed as transgressive. The more-established and more strongly held these community values are, the better a job of matching your reputation systems inputs and rewards to those values you must do.

- With some communities, you may already be running into problems of scale that you would not encounter with an early-stage or brand new site. There might already be an overwhelming amount of conversation (or noise, depending on how you look at it.) And you could be faced with migration issues:

- Should you 'grandfather' old content, and just leave it out of the new system?

- Will you expect people to go back and retroactively grade old content? (In all likelihood, they won't.)

- In particular, changes to an existing reputation system may be difficult. Whether as trivial and opaque as tweaking some of the parameters that determine a video's “popularity” or as visible and significant as introducing a new level designation for top performers, you are likely to encounter resistance (or at the very least, curiosity) from your community. You are, in effect, changing the rules for your community, so expect the typical reaction: some will welcome the changes, others (typically, those who benefited most under the old rules) will denounce them.

We don't mean to imply, however, that designing a reputation system for a new “green-field” community is an easy task: in these circumstances, rather than identifying the characteristics of your community that you'd like to enhance (or leave unharmed), your task will be to imagine the community effects that you're hoping to influence, then make smart decisions to affect those outcomes. In any event, it is always worthwhile to consider…

What is your community's character? What would you like it to be?

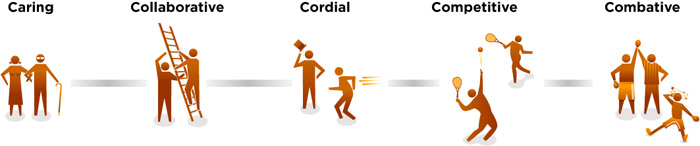

Is your community a friendly, welcoming place? Helpful? Collaborative? Argumentative or spirited? Downright combative? Communities can display a whole range of behaviors and it can be dangerous to generalize too much about any specific community, but you must at least consider the overall character of the community that your reputation system seeks to influence.

The Competitive Spectrum

Though it's not the only aspect worth considering, a very telling one is the level of perceived competitiveness in your community: the individual goals of community members, and to what degree those goals coexist peacefully, or conflict; the actions that community-members engage in, and to what degree those actions may impinge on the experiences of other community-members; and to what degree inter-person comparisons or contests are desired.

In general, more competitive a group of people in a community are, the more appropriate it is to compare those people (and the artifacts that they generate) against each other.

Read that last bit again, and carefully! A common mistake that product architects (especially for social web experiences) make is assuming that a higher level of competitiveness exists than what's really there. Because reputation systems and their attendant incentive systems are often intended to emulate the principles of engaging game designs, designers often gravitate toward the aggressively competitive-and comparative-end of the spectrum.

Even the intermediate stages along the spectrum can be deceiving. For example, where would you place a community like Match.com or Yahoo! Personals along the spectrum? Perhaps your first instinct was to say “I would place a dating site firmly at the 'Competitive' stage of the spectrum.” I mean, people are competing for attention, right? And dates?

Remember, though, the entire context for reputation in this example. Most importantly, remember the desires of the person doing the evaluating on these sites. A visitor to a dating site probably doesn't want a competition, nor does she view it that way: for her, this site may be a more collaborative endeavor. She's looking for a potential dating partner across her own particular set of criteria and needs. Not necessarily 'the best person on the site.'

Better Questions

Remember, our goal for this chapter has been to get you asking the right questions about reputation for your application or site. Do I need reputation at all? How might it promote more and better participation? How might it conflict with my goals for the community of use around my site? We've given you a lot to consider in this chapter, but the answers to these questions will be genuinely invaluable as we begin to dig into the nuts and bolts of your reputation system in Chapter_7 .